| Feb 19, 2019 |

Hundreds of thousands of new galaxies

|

|

(Nanowerk News) An international team of more than 200 astronomers from 18 countries has published the first phase of a major new radio sky survey at unprecedented sensitivity using the Low Frequency Array (LOFAR) telescope ("LOFAR Surveys", 26 papers in special issue of Astronomy and Astrophysics). The survey reveals hundreds of thousands of previously undetected galaxies, shedding new light on many research areas including the physics of black holes and how clusters of galaxies evolve.

|

|

Radio astronomy reveals processes in the Universe that we cannot see with optical instruments. In this first part of the sky survey, LOFAR observed a quarter of the northern hemisphere at low radio frequencies. At this point, approximately ten percent of that data is now made public. It maps three hundred thousand sources, almost all of which are galaxies in the distant Universe; their radio signals have travelled billions of light years before reaching Earth.

|

|

| LOFAR station Effelsberg, shown from 50 m above ground. In front: LOFAR lowband antennas (LBA) for 10-80 MHz, in the back: LOFAR highband antennas (HBA) for 110-240 MHz. (Image: W. Reich/MPIfR)

|

Black holes

|

|

Huub Röttgering, Leiden University (The Netherlands): “If we take a radio telescope and we look up at the sky, we see mainly emission from the immediate environment of massive black holes. With LOFAR we hope to answer the fascinating question: where do those black holes come from?” What we do know is that black holes are pretty messy eaters. When gas falls onto them they emit jets of material that can be seen at radio wavelengths.

|

|

Philip Best, University of Edinburgh (UK), adds: “LOFAR has a remarkable sensitivity and that allows us to see that these jets are present in all of the most massive galaxies, which means that their black holes never stop eating.”

|

Clusters of galaxies

|

|

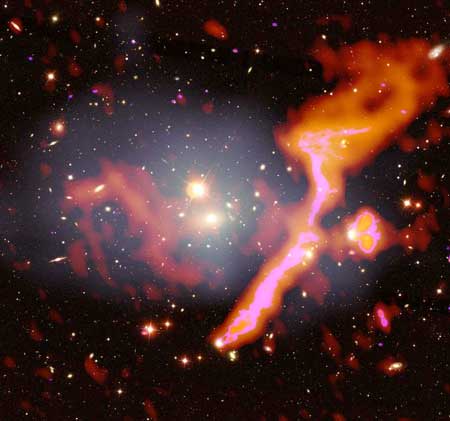

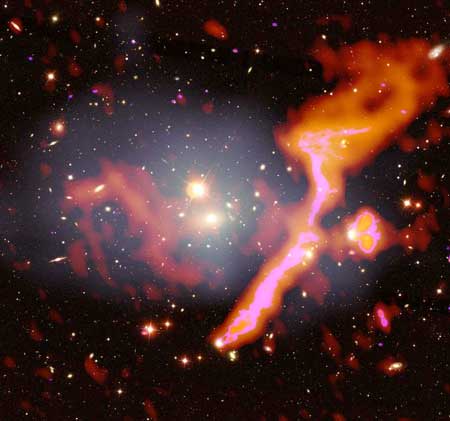

Clusters of galaxies are ensembles of hundreds to thousands of galaxies and it has been known for decades that when two clusters of galaxies merge, they can produce radio emission spanning millions of light years. This emission is thought to come from particles that are accelerated during the merger process.

|

|

Amanda Wilber, University of Hamburg (Germany), elaborates: “With radio observations we can detect radiation from the tenuous medium that exists between galaxies. This radiation is generated by energetic shocks and turbulence. LOFAR allows us to detect many more of these sources and understand what is powering them."

|

|

Annalisa Bonafede, University of Bologna and INAF (Italy), adds: “What we are beginning to see with LOFAR is that, in some cases, clusters of galaxies that are not merging can also show this emission, albeit at a very low level that was previously undetectable. This discovery tells us that, besides merger events, there are other phenomena that can trigger particle acceleration over huge scales.”

|

|

| Galaxy cluster Abell 1314 with radio emission from high-speed cosmic electrons (marked in red) overlayed onto an optical image also showing hot X-ray gas (marked in grey). (Image: Amanda Wilber/LOFAR Surveys Team)

|

Magnetic fields

|

|

The unprecedented accuracy of the LOFAR measurements allows to measure the effect of cosmic magnetic fields on radio waves. Researchers from Germany investigated magnetic fields in the halos of galaxies. They could show the existence of enormous magnetic structures also between galaxies. „The LOFAR data are providing hints that the space between galaxies could be completely magnetic“, says Rainer Beck from MPIfR Bonn, Germany.

|

High-quality images

|

|

Creating low-frequency radio sky maps takes both significant telescope and computational time and requires large teams to analyse the data. “LOFAR produces enormous amounts of data - we have to process the equivalent of ten million DVDs of data. The LOFAR surveys were recently made possible by a mathematical breakthrough in the way we understand interferometry”, says Cyril Tasse, Observatoire de Paris - Station de radioastronomie à Nançay (France).

|

|

“We have been working together with SURF in the Netherlands to efficiently transform the massive amounts of data into high-quality images. These images are now public and will allow astronomers to study the evolution of galaxies in unprecedented detail”, says Timothy Shimwell, Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) and Leiden University.

|

|

SURF's compute and data centre located at SURFsara in Amsterdam runs on 100 percent renewable energy and hosts over 20 petabytes of LOFAR data. “This is more than half of all data collected by the LOFAR telescope to date. It is the largest astronomical data collection in the world. Processing the enormous data sets is a huge challenge for scientists. What normally would have taken centuries on a regular computer was processed in less than one year using the high throughput compute cluster (Grid) and expertise”, says Raymond Oonk (SURFsara).

|

LOFAR

|

|

The LOFAR telescope, the Low Frequency Array, is unique in its capabilities to map the sky in fine detail at metre wavelengths. LOFAR is operated by ASTRON in The Netherlands and is considered to be the world’s leading telescope of its type. “This sky map will be a wonderful scientific legacy for the future. It is a testimony to the designers of LOFAR that this telescope performs so well”, says Carole Jackson, Director General of ASTRON.

|

The next step

|

|

The 26 research papers in the special issue of Astronomy & Astrophysics were done with only the first two percent of the sky survey. The team aims to make sensitive high-resolution images of the whole northern sky, which will reveal 15 million radio sources in total. “Just imagine some of the discoveries we may make along the way. I certainly look forward to it”, says Jackson. “And among these there will be the first massive black holes that formed when the Universe was only a ‘baby’, with an age a few percent of its present age”, adds Röttgering.

|