| Jun 14, 2022 |

Scientists on the hunt for planetary formation fossils reveal unexpected eccentricities in nearby debris disk

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), astronomers have imaged the debris disk of the nearby star HD 53143 at millimeter wavelengths for the first time, and it looks nothing like they expected. Based on early coronagraphic data, scientists expected ALMA to confirm the debris disk as a face-on ring peppered with clumps of dust. Instead, the observations took a surprise turn, revealing the most complicated and eccentric debris disk observed to date.

|

|

The observations were presented today in a press conference at the 240th meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS) in Pasadena, California, and will be published in an upcoming edition of The Astrophysical Journal Letters ("ALMA Images the Eccentric HD 53143 Debris Disk").

|

|

HD 53143— a roughly billion-year-old Sun-like star located 59.8 light-years from Earth in the Carina constellation— was first observed with the coronagraphic Advanced Camera for Surveys on the Hubble Space Telescope (HST) in 2006. It also is surrounded by a debris disk—a belt of comets orbiting a star that are constantly colliding and grinding down into smaller dust and debris— that scientists previously believed to be a face-on ring similar to the debris disk surrounding our Sun, more commonly known as the Kuiper Belt.

|

|

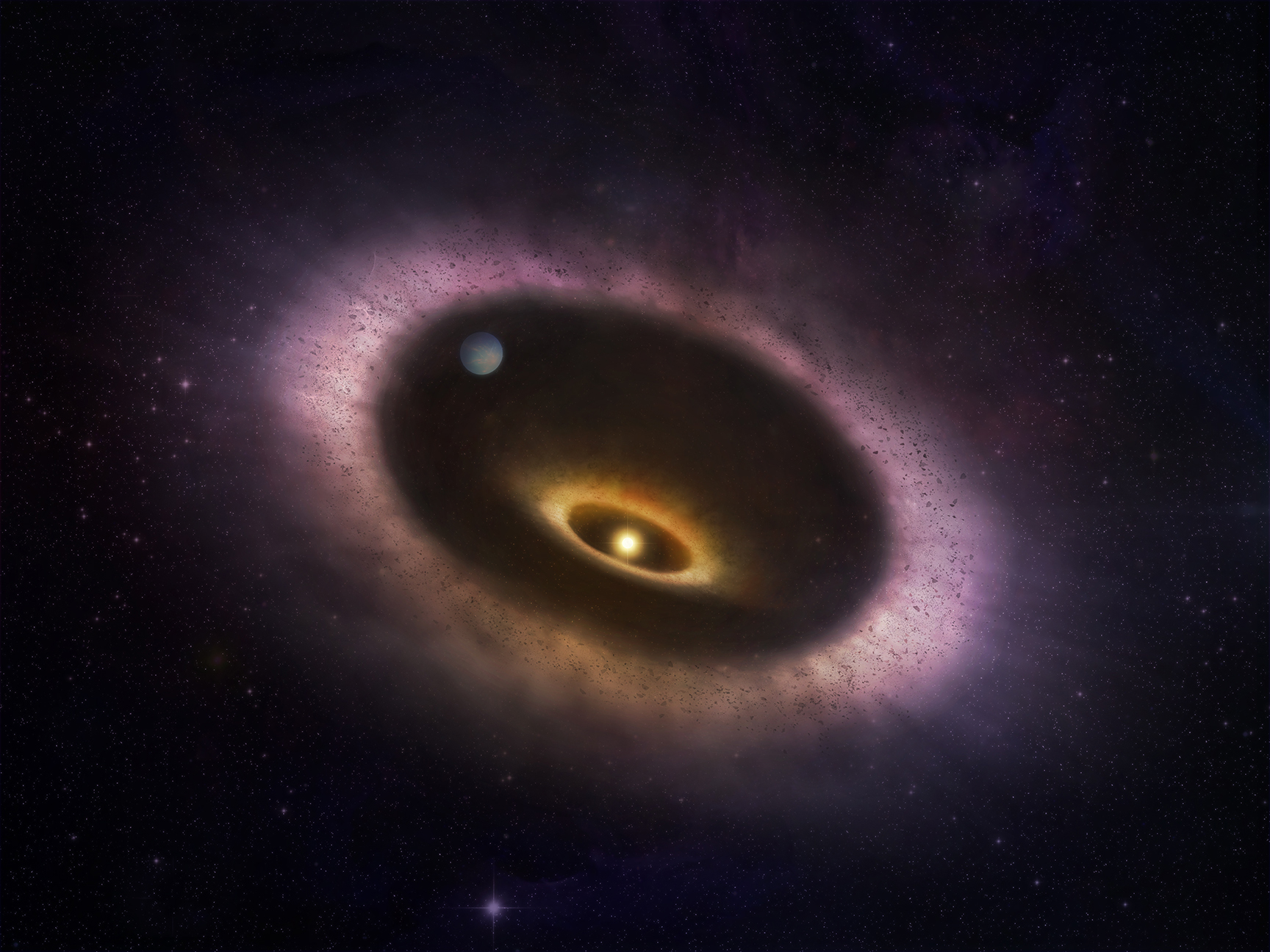

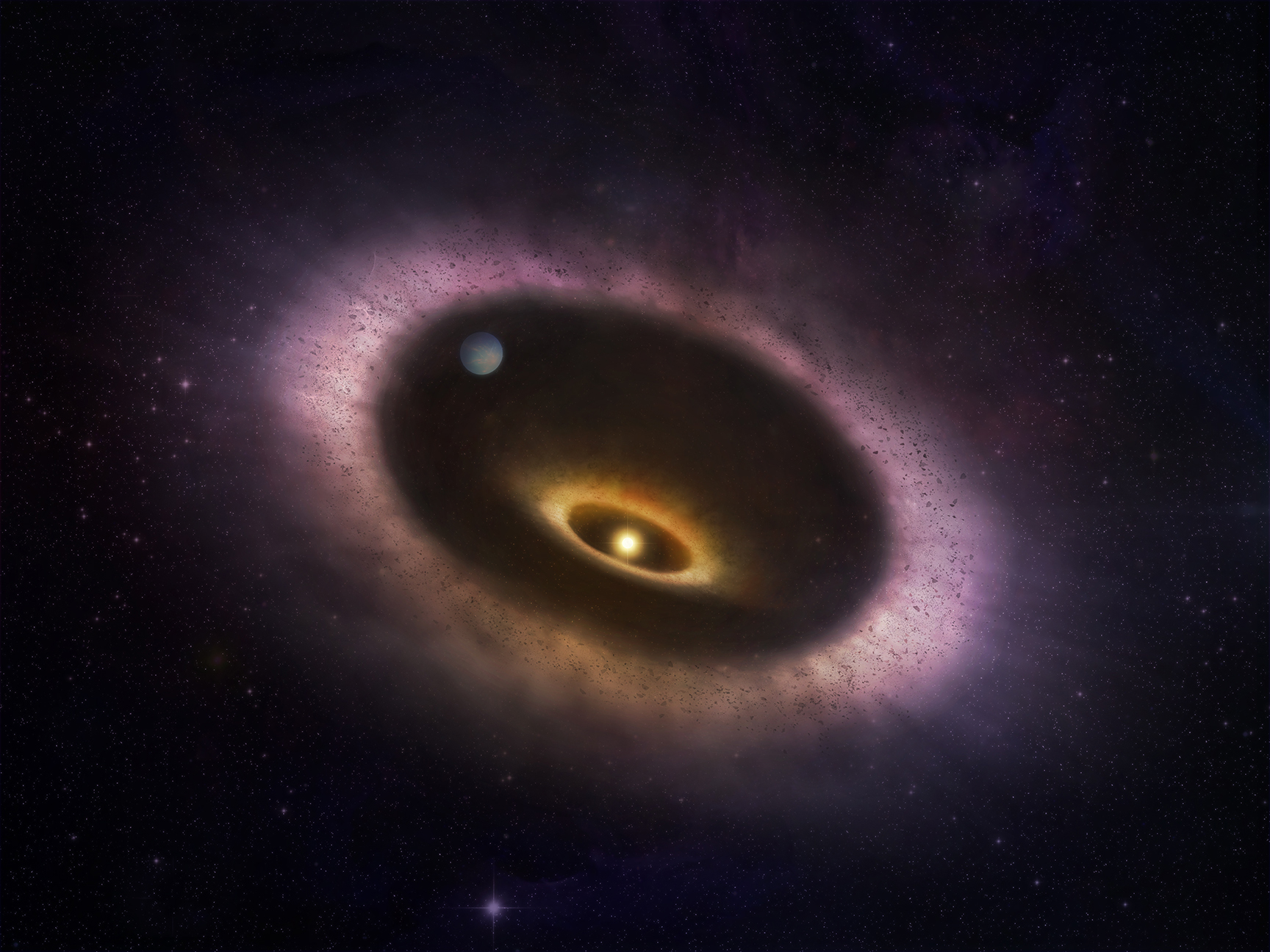

| Artist’s impression of the billion-year-old Sun-like star, HD 53143, and its highly eccentric debris disk. The star and a second inner disk are shown near the southern foci of the elliptical debris disk. A planet, which scientists assume is shaping the disk through gravitational force, is shown to the north. Debris disks are the fossils of planetary formation and since we can’t directly study our own disk— also known as the Kuiper Belt— scientists glean information about the formation of our Solar System by studying those we can see from a distance. (Image: ALMA (ESO/NAOJ/NRAO); M. Weiss (NRAO/AUI/NSF))

|

|

The new observations were made of HD 53143 using the highly-sensitive Band 6 receivers on ALMA, an observatory co-operated by the U.S. National Science Foundation’s National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), and have revealed that the star system’s debris disk is actually highly eccentric. In ring-shaped debris disks, the star is typically located at or near the center of the disk. But in elliptically-shaped eccentric disks, the star resides at one focus of the ellipse, far away from the disk’s center. Such is the case with HD 53143, which wasn’t seen in previous coronagraphic studies because coronagraphs purposely block the light of a star in order to more clearly see nearby objects. The star system may also be harboring a second disk and at least one planet.

|

|

“Until now, scientists had never seen a debris disk with such a complicated structure. In addition to being an ellipse with a star at one focus, it also likely has a second inner disk that is misaligned or tilted relative to the outer disk,” said Meredith MacGregor, an assistant professor at the Center for Astrophysics and Space Astronomy (CASA) and Department of Astrophysical and Planetary Sciences (APS) at CU Boulder, and the lead author on the study. “In order to produce this structure, there must be a planet or planets in the system that are gravitationally perturbing the material in the disk.”

|

|

This level of eccentricity, MacGregor said, makes HD 53143 the most eccentric debris disk observed to date, being twice as eccentric as the Fomalhaut debris disk, which MacGregor fully imaged at millimeter wavelengths using ALMA in 2017. “So far, we have not found many disks with a significant eccentricity. In general, we don’t expect disks to be very eccentric unless something, like a planet, is sculpting them and forcing them to be eccentric. Without that force, orbits tend to circularize, like what we see in our own Solar System.”

|

|

Importantly, MacGregor notes that debris disks aren’t just collections of dust and rocks in space. They are a historical record of planetary formation and how planetary systems evolve over time. and provide a peek into their futures. “We can’t study the formation of Earth and the Solar System directly, but we can study other systems that appear similar to but younger than our own. It’s a bit like looking back in time,” she said. “Debris disks are the fossil record of planet formation, and this new result is confirmation that there is much more to be learned from these systems and that knowledge may provide a glimpse into the complicated dynamics of young star systems similar to our own Solar System.”

|

|

Dr. Joe Pesce, NSF program officer for ALMA, added, "We are finding planets everywhere we look, and these fabulous results by ALMA are showing us how planets form - both those around other stars and in our own Solar System. This research demonstrates how astronomy works and how progress is made, informing not only what we know about the field but also about ourselves."

|