| Dec 14, 2018 | |

Scientists design custom nanoparticles with new 'stencil' method(Nanowerk News) Nanoparticles already make bicycles and tennis rackets lighter and stronger, protect eyeglasses from scratches, and help direct chemotherapy drugs to cancer cells. But their usefulness depends on being able to precisely sculpt them into the right configurations—no easy task when they’re so tiny that thousands of them could fit into the thickness of a sheet of paper. |

|

| In a study published in Nature Materials ("Regioselective surface encoding of nanoparticles for programmable self-assembly"), University of Chicago scientists unveiled an innovative technique to push the boundaries of making such nanoparticles. They apply a coating which covers up parts of the nanoparticle, which allows them to coat new molecules on only the exposed surfaces—a bit like a stencil and a can of spray paint. | |

|

|

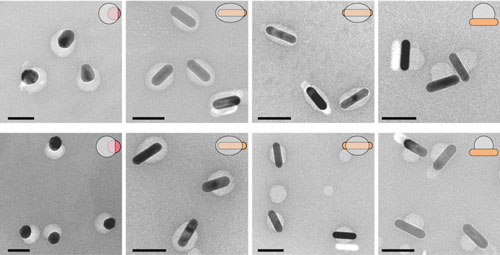

| A new technique allows scientists to build custom coats for nanoparticles in all kinds of specific shapes (demonstrated in the top right for each box). They are so small that thousands could fit in the period at the end of this sentence. (Image: Chen and Gibson et al.) (click on image to enlarge) | |

| Nanoparticles are fascinating because they like to assemble themselves into shapes, so for a lot of applications, scientists can add the right ingredients and bake it at the right temperatures to get the shapes they want. But that only yields a certain range of possibilities. | |

| “Most self-assembly is based on spheres, which don’t really have a difference in structure, but with most other shape it’s important to be able to get to specific areas,” said Yossi Weizmann, an assistant professor of chemistry and author on the paper. “You need deeper capabilities to more fully explore the possibilities of nanotechnology.” | |

| The new method uses a coating of polymer spackled onto the nanoparticles in certain spots. Then you can add the next molecule, which can only attach to the nanoparticles where there is no polymer. | |

| The resulting possibilities are only limited to a scientist’s imagination. | |

| “The way we designed the building blocks lets you make a great number of permutations,” said graduate student Kyle Gibson, co-first author on the paper. | |

| They tested it and made a variety of shapes in nano-size—3-D cubes with only centers or edges and vertices exposed, 2-D prisms with free corners, and one-dimensional rods with only one side or one or both ends available. | |

| The range of shapes allows scientists to experiment with properties, the scientists said, which could yield ideas for new electronics and sensing. |

| Source: By Louise Lerner, University of Chicago | |

|

Subscribe to a free copy of one of our daily Nanowerk Newsletter Email Digests with a compilation of all of the day's news. |