| Posted: October 6, 2009 |

Yoctosecond flashes from ultra-hot matter |

|

(Nanowerk News) High-energy heavy ion collisions, which are studied at RHIC in Brookhaven and soon at the LHC in Geneva, can be a source of light flashes of a few yoctoseconds duration (a septillionth of a second, 10-24 s, ys) - the time that light needs to traverse an atomic nucleus. This is shown in calculations of the light emission of so-called quark-gluon plasmas, which are created in such collisions for extremely short periods of time. Under certain conditions, double flashes are created, which could be utilized in the future to visualize the dynamics of atomic nuclei ("Yoctosecond Photon Pulses from Quark-Gluon Plasmas")

|

|

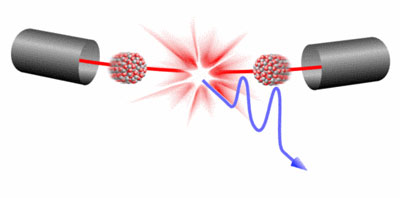

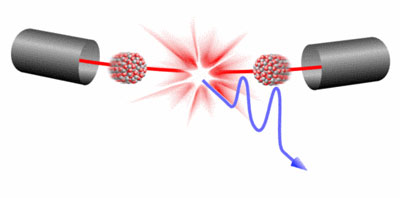

| Collisions of heavy ions in a large accelerator facility (schematic). Under certain conditions, double light flashes of a few yoctoseconds duration can be emitted.

|

|

For high-precision spectroscopy and structural studies of molecules, short light flashes with lowest possible wavelength, i.e., high photon energy, are required. Currently, x-ray flashes of some attosecond (a quintillionth of a second, 10-18 s) duration are accessible experimentally. Even shorter pulses with even higher photon energy would improve the temporal and spatial resolution, or would allow for the investigation of even smaller structures, such as for example atomic nuclei. In so-called pump-probe experiments, two light pulses of exactly controllable distance are utilized to observe rapid system changes in slow motion.

|

|

Calculations at the Max Planck Institute for Nuclear Physics have now shown that high-energy heavy ion collisions at large particle accelerators are suitable as light sources for the desired single and double pulses. This is due to the remarkable properties of quark-gluon plasmas.

|

|

The quark-gluon plasma is a state of matter of which the universe consisted right after the big bang. In this state, the temperatures are so high that even the constituents of atomic nuclei, the neutrons and protons, are split into their constituents, the quarks and gluons. Such a state of matter can nowadays be realized in modern colliders.

|

|

|

|

In the collision of heavy ions (i.e. atoms of heavy elements from which all electrons have been removed) at relativistic velocities, such a quark-gluon plasma is created for a few yoctoseconds at the size of a nucleus. Among many other particles, it also creates photons of a few GeV (billion electron volts) energy, so-called gamma radiation. These high-energy flashes of light are as short as the lifetime the quark-gluon plasma and consist of only a few photons.

|

|

The researchers have simulated the time-dependent expansion and internal dynamics of the quark-gluon plasma. It was found that at some intermediate time the photons are not emitted in all directions, but preferably perpendicular to the collision axis. A detector that is placed close to the collision axis will measure practically nothing during this period. Therefore, overall it detects a double pulse. By suitable choice of geometry of the setup and observing direction, the double pulses can in principle be selectively varied. Thus, they open up the possibility of future pump-probe experiments in the yoctosecond range at high energies. This could lead to a time-resolved observation of processes in atomic nuclei. Conversely, a detailed analysis of the gamma-ray flashes would allow to draw conclusions about the quark-gluon plasma.

|