| Posted: Jun 13, 2006 | |

Acoustic sensors made from magnetic nanowires |

|

| (Nanowerk Spotlight) Researchers took inspiration from the packaging and transduction processes of the cochlea and cilia in the inner ear to design acoustic sensors made from nanowires. Specifically, they used nanowires of magnetostrictive materials as artificial cilia to sense acoustic signals. Any acoustic sensor application may benefit from this work. | |

| Professor Beth Stadler and members of her group from the Department of Electrical Engineering at the University of Minnesota, together with scientists from Aerospace Engineering at the University of Maryland, led by Professor Alison Flatau, are the first to use nanowires for acoustic sensors and also pioneered making nanowires out of Galfenol, the latest magnetostrictive material to be invented. | |

| Their work has been reported in a paper, titled "Magnetic nanowires for acoustic sensors", in the April 15, 2006 edition of the Journal of Applied Physics. | |

| "We have been able to produce both magnetostrictive and magnetoresistive nanowires" Stadler explains to Nanowerk. "These can be used anywhere from hearing to sonar to medical imaging. Their small size may prove especially useful in medical applications where an ultrasound image could be taken from inside a nearby blood vessel. Also, because they are small and are also made in close-packed arrays, a very sensitive sensor with high bandwidth can be made in a small area." | |

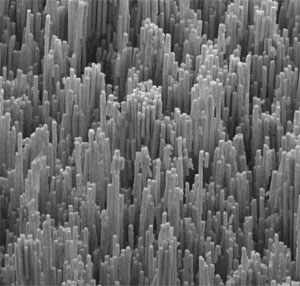

| The magnetostrictive nanowires made in the recent experiments were fabricated using electrochemical deposition into nanoporous AAO templates. High aspect ratio nanowires with diameters varying from 10 to 200 nm and lengths up to 60 µm were fabricated in arrays and were collectively and individually characterized using scanning electron microscopy. | |

| The nanowires were grown from Ni, Co, and a new material called Galfenol, which is a gallium-iron alloy. Galfenol exhibits high sensitivity, generating a significant magnetic field in response to a signal, and yet it has the excellent mechanical properties of iron. | |

|

SEM image of Ni nanowires from which the aluminum oxide matrix was partially removed. (Source: University of Minnesota) |

| "The Ni and Co nanowire fabrication was straightforward" says Stadler, "but electrochemically depositing Fe–Ga alloys with controlled stoichiometries proved extremely difficult. Therefore, thin-film deposition was used to study the electrochemistry and co-deposition of Fe and Ga. The goal was to find an electrochemical recipe which would allow the stoichiometry of Fe1-xGax alloys to be precisely tuned by both the metal ion concentrations and the deposition potential." | |

| To build on these results, Stadler says she would like to take the nanowire arrays they are currently able to produce and get them into devices soon: "We have a lot of exploration to do regarding the best materials for the job, such as optimizing the Ga/Fe ratio in the Galfenol and the multilayers in the magnetoresistive sensors." | |

By

Michael

Berger

– Michael is author of three books by the Royal Society of Chemistry:

Nano-Society: Pushing the Boundaries of Technology,

Nanotechnology: The Future is Tiny, and

Nanoengineering: The Skills and Tools Making Technology Invisible

Copyright ©

Nanowerk LLC

By

Michael

Berger

– Michael is author of three books by the Royal Society of Chemistry:

Nano-Society: Pushing the Boundaries of Technology,

Nanotechnology: The Future is Tiny, and

Nanoengineering: The Skills and Tools Making Technology Invisible

Copyright ©

Nanowerk LLC

|

|

Become a Spotlight guest author! Join our large and growing group of guest contributors. Have you just published a scientific paper or have other exciting developments to share with the nanotechnology community? Here is how to publish on nanowerk.com.