| Aug 26, 2011 |

Dynamics of coupled magnetic vortices

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Crystals can guide and control light and electricity by creating spatially periodic energy barriers. An electron (or photon) can pass through these barriers only when it has a particular energy, allowing engineers to create switches and other electronic devices. Now, a team of researchers from Japan and India has taken a key step towards using crystals to control waves of magnetic orientation (magnons), with the potential to create magnetic analogues to electronic and optical devices, including memory devices and transistors ("Dynamics of Coupled Vortices in a Pair of Ferromagnetic Disks").

|

|

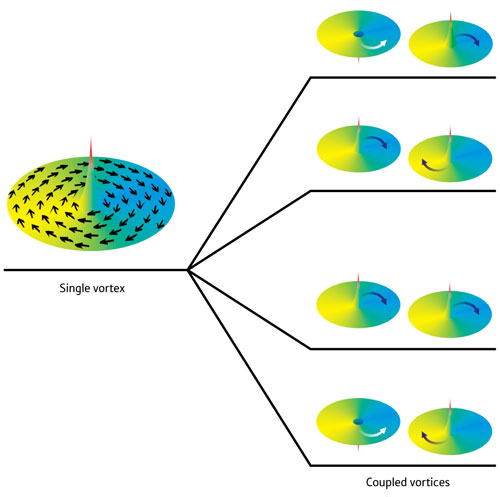

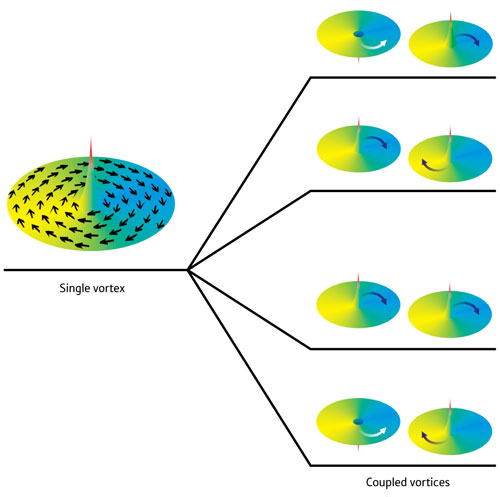

| Figure 1: The magnetic domains in a single ferromagnetic disk arrange into a vortex (left). When two disks are brought close together (right), the magnetic vortices begin to move together. Their motion can be in-phase (bottom two levels), or out of phase (top two). The vortex cores can also point in the same direction, or in opposite directions, leading to four possible types of coupled motion. (© APS)

|

|

Led by YoshiChika Otani at the RIKEN Advanced Science Institute, Wako, the researchers began by manufacturing tiny disks of ferromagnetic material. The magnetic domains of such disks arrange into vortices (Fig. 1, left), which consist of in-plane circular patterns surrounding a core with out-of-plane magnetization. By applying an alternating current with a particular frequency to such disks, physicists can excite the vortices into a gyrating motion, which they can detect by measuring the voltage across a disk.

|

|

Otani and his colleagues found that a current oscillating at 352 megahertz could set the vortex of a single disk into motion. When they brought a second disk near the first one, however, this single resonant frequency split into two: one was lower than the original frequency, and the other was higher. This kind of resonance splitting is characteristic of any pair of interacting oscillators with similar energies, whether it be two molecules that are covalently bonded to each other, or two swinging pendula.

|

|

The frequency splitting observed in the researchers' pair of disks indicated that the magnetic vortices in each were coupled together, even though the current was driving one disk only. The researchers showed through numerical simulation that the lower-frequency resonance corresponded to the two vortices rotating in phase with each other; the higher-frequency resonance corresponded to an out-of-phase rotation. Depending on whether the core polarizations of the two disks were pointing in the same or opposite directions, Otani and colleagues also observed different frequency pairs. This led to four distinct resonant frequencies in all (Fig. 1, right).

|

|

The researchers could control the differences among the four resonant frequencies by changing the distance between disks, as well as the disk sizes. By demonstrating controllable pairing between adjacent magnetic vortices, the results point the way to more complex chains, lattices and crystals in which magnons can be finely controlled, says Otani. "Our next target is to engineer a structure in which macroscopic spin waves propagate only along particular crystallographic directions."

|