| Jun 15, 2017 |

A signal of safe therapy

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Stem cells have paved the way for a new era in regenerative medicine, but their use is fraught with risk. Now, A*STAR scientists have developed an antibody that could make stem cell therapy safer (Cell Death & Differentiation, "Excess reactive oxygen species production mediates monoclonal antibody-induced human embryonic stem cell death via oncosis").

|

|

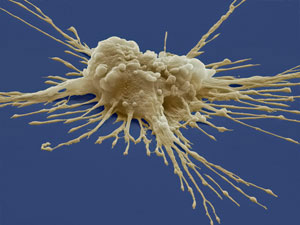

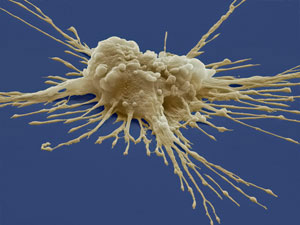

Human pluripotent stem cells that can differentiate in a petri dish to become any cell needed to repair tissues and organs, hold great promise. Since the first human embryonic stem cells were isolated in 1998, scientists have edged closer to developing ‘cell therapy’ for humans. In early 2017, a Japanese man became the first patient to receive a retina transplant made of reprogrammed pluripotent stem cells to treat macular degeneration.

|

|

| Stem cells (pictured) hold great promise, as well as risk, for regenerative medicine. (Image: Steve Gschmeissner/Brand X Pictures/Getty)

|

|

These potential rewards come with great risk. Differentiating stem cells into other cell types is an imperfect process, and any stem cells that remain in a culture of transplanted cells can form dangerous by-products, including tumors, such as teratomas.

|

|

“If stem cells become a cell therapy product there will be the question of safety,” Andre Choo, from the A*STAR Bioprocessing Technology Institute, explains.

|

|

Choo and his team are working to make stem cell treatments safer by creating antibodies that ‘clean up’ the pluripotent stem cells which fail to differentiate.

|

|

In 2016, the researchers used a whole-cell immunization strategy to generate different antibodies by injecting mice with viable embryonic stem cells. They then isolated the antibodies and tested their ability to search and destroy pluripotent stem cells in a culture dish.

|

|

One antibody, tagged ‘A1’, was discovered which destroyed pluripotent stem cells in minutes but left other cells unharmed.

|

|

Choo’s team then focused on how the antibody destroyed its target. The scientists discovered that A1 docks to sugar molecules that are only present on the surface of embryonic stem cells, setting off a signaling cascade that ruptures the stem cell.

|

|

“That was quite exciting because it now gives us a view of the mechanism that is responsible for the cell-killing effect,” says Choo.

|

|

Understanding this mechanism could allow Choo’s team to combine the A1 antibody with other treatments to clean stem cells from a mixture of differentiated cells even more effectively.

|

|

The finding could also pinpoint how best to target antibodies against sugar molecules on other unwanted cells, including cancer cells.

|

|

“We hope that in the near future regenerative medicine will have a place in the clinic,” says Choo, who wants this antibody to be part of that process.

|