| Dec 02, 2014 |

Missing ingredient in energy-efficient buildings: People

|

|

(Nanowerk News) More than one-third of new commercial building space includes energy-saving features, but without training or an operator’s manual many occupants are in the dark about how to use them.

|

|

Julia Day recently published a paper in Building and Environment ("Understanding high performance buildings: The link between occupant knowledge of passive design systems, corresponding behaviors, occupant comfort and environmental satisfaction") that for the first time shows that occupants who had effective training in using the features of their high-performance buildings were more satisfied with their work environments. Day did the work as a doctoral student at Washington State University; she is now an assistant professor at Kansas State University.

|

|

Closed blinds open research path

|

|

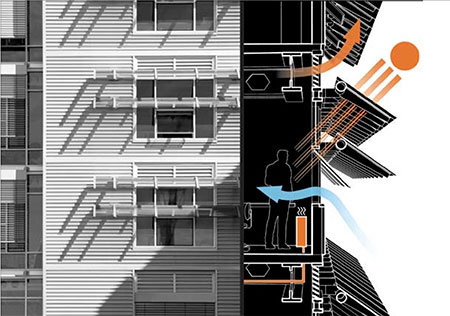

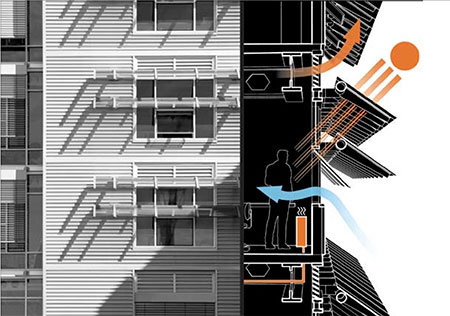

She was a WSU graduate student in interior design when she walked into an office supposedly designed for energy efficiency and noticed that the blinds were all closed and numerous lights were turned on. The building had been designed to use daylighting strategies to save energy from electric lighting.

|

|

After inquiring, Day learned that cabinetry and systems furniture throughout the building blocked nearly half of the occupants from access to the blind controls. Only a few determined folks would climb on or under their desks to operate the blinds.

|

|

“People couldn’t turn off their lights, and that was the whole point of implementing daylighting in the first place,” she said. “The whole experience started me on my path.”

|

|

Ventilation indicators mistaken for fire-alarm lights

|

|

Working with David Gunderson, professor in the WSU School of Design and Construction, Day looked at more than 50 high-performance buildings across the U.S. She gathered data, including their architectural and engineering plans, and did interviews and surveys of building occupants.

|

|

|

She examined how people were being trained in the buildings and whether their training was effective. Sometimes, she learned, the features were simply mentioned in a meeting or a quick email was sent to everyone, and people did not truly understand how their actions could affect the building’s overall energy use.

|

|

One LEED gold building had lights throughout to indicate the best times of day to open and close windows to take advantage of natural ventilation. A green light indicated it was time to open windows.

|

|

“I asked 15 people if they knew what the light meant, and they all thought it was part of the fire alarm system,’’ she said. “There’s a gap, and people do not really understand these buildings.’’

|

|

Efficient commercial space expanding

|

|

According to CBRE Research, the amount of commercial space that is certified as high-performance in energy efficiency through the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star or U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED has grown from 5.6 percent of commercial space in 2005 to 39.3 percent at the end of 2013.

|

|

Yet in many cases, the corporate culture of energy use in buildings hasn’t caught up. While at home our mothers nagged us to turn off the lights when we left a room or to shut the door because “you don’t live in a barn,” office culture has often ignored and even discouraged common-sense energy saving.

|

|

Educating for an energy-focused culture

|

|

Day found that making the best use of a highly efficient building means carefully creating a culture focused on conservation. In buildings with an energy-focused culture, workers were engaged, participated and were satisfied with their building environment.

|

|

“If they received good training, they were more satisfied and happier with their work environment,’’ she said.

|

|

She is working to develop an energy lab and would like to develop occupant training programs to take advantage of high-performance buildings.

|

|

“With stricter energy codes, the expectations are that buildings will be more energy efficient and sustainable,’’ she said. “But we have to get out of the mindset where we are not actively engaged in our environments. That shift takes a lot of education, and there is a huge gap right now.”

|