| Jan 31, 2020 |

Breaking through computational barriers to create designer proteins

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Designing proteins is a massive combinatorial problem. Scientists must consider how protein building blocks, amino acids, interact with each other in ways that drive their spatial position and orientation, resulting in 3D protein structures. Then, they use a protein design algorithm to find proteins that perfectly pair with each other.

|

|

This is particularly difficult when looking, among a database of [thousands/millions], for combinations of two different proteins that exclusively bind to one another. These protein pairs must have backbone shapes that only complement each other. Using advanced computational methods to find working designs, researchers created six protein pairs of this type in cells.

|

|

If scientists could engineer pairs of proteins that bind only to one another, they could have much more control over cells in living systems. This ability could enable bioengineering applications with large impacts for medicine and biomaterials.

|

|

Currently, scientists can only design DNA (not proteins themselves) to form these interactions. Being able to encode DNA gave rise to technologies such as DNA origami and artificial circuits. A general method for creating protein pairs would also be very powerful, opening the door to many more possibilities.

|

|

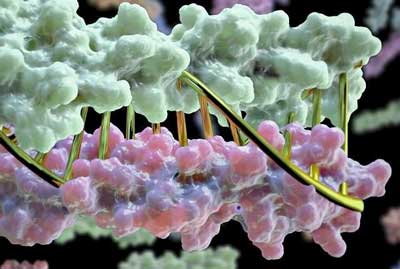

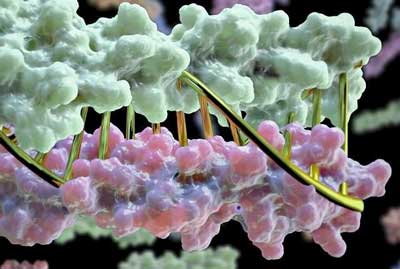

| A designed coiled-coil heterodimer, with halves colored green and purple. A DNA double-helix (gold), for which particular sequences have the same property of forming specific pairs, is superimposed to show scale. (Image: Institute for Protein Design.)

|

|

This work (Nature, "Programmable design of orthogonal protein heterodimers") used the Rosetta software, which has a long history of being used for protein modeling, analysis, and design. Past helical bundle design work had focused on single-molecule bundles or on homooligomers (assemblies of many copies of the same molecule).

|

|

With the pairing of two proteins, the coiled-coil parameter space is incredibly vast. Using the Rosetta software suite, the team used the Mira supercomputer at Argonne National Laboratory to sample conformations efficiently, through a massively parallelized grid search of 11 parameters, to find 87 million (20 million untwisted and 60 million left-handed supercoiled) unique working designs for four-helix backbones (35 residues each).

|

|

The team then exhaustively searched for unique hydrogen bonded networks that connected all four helices finding 2,251 unique networks. Low-energy sequences were then identified using the RosettaDesign server to test compatible placements of the hydrogen-bonded networks within all four-helix candidates.

|

|

Of the 97 computationally selected designs that were stable and satisfied additional criteria, 94 were well-expressed in E. coli, 85 had the expected size as measured with size-exclusion chromatography, 65 formed constitutive heterodimers, and 39 where exclusive heterodimers. Four designs were selected to be validated against experimental data using x-ray crystallography. Those were found to be in good agreement with the computational models, and confirmed the predicted hydrogen bond networks that were designed into the structure.

|

|

The team also investigated rearranging the hydrogen-bond networks in different helical repeat units to expand the heterodimer set. This was largely successful, with generation of 22 new constitutive heterodimers. In the end, the team created six fully orthogonal protein heterodimer pairs in E. coli cells. This work provides a path forward for one to computationally design specific, programmable binding into proteins, previously a property only found in the DNA and RNA world.

|