| Aug 23, 2021 |

Researchers build world's smallest biomechanical linkage

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Researchers at Princeton University have built the world's smallest mechanically interlocked biological structure, a deceptively simple two-ring chain made from tiny strands of amino acids called peptides.

|

|

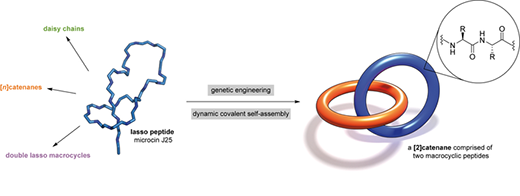

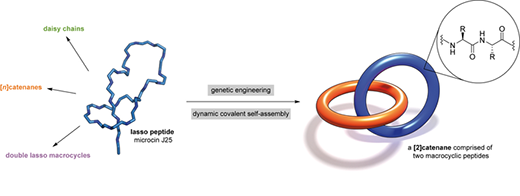

In a paper published in Nature Chemistry ("Dynamic covalent self-assembly of mechanically interlocked molecules solely made from peptides"), the team detailed a library of such structures made in their lab—two interlocked rings, a ring on a dumbbell, a daisy chain and an interlocked double lasso—each around one billionth of a meter in size. The study also demonstrates that some of these structures can toggle between at least two shapes, laying the groundwork for a biomolecular switch.

|

|

"We've been able to build a bunch of structures that no one's been able to build before," said A. James Link, professor of chemical and biological engineering, the study's principal investigator. "These are the smallest threaded or interlocking structures you can make out of peptides."

|

|

| By engineering a naturally occurring lasso peptide, Princeton University researchers have created the world's first and smallest interlocking biomechanical structure. (Image: Hendrik V. Schröder and A. James Link) (click on image to enlarge)

|

|

To craft these gadgets, dubbed mechanically interlocked peptides, or MIPs, the researchers used genetic engineering to manipulate individual amino acids in a naturally occurring lasso peptide, microcin J25, and direct the peptide to self-assemble into new shapes.

|

|

They also bypassed the need for the harsh solvents and metal ions used in building similar synthetic molecular architectures, work that was the focus of the 2016 Nobel Prize in chemistry. This work, using a single-pot protocol in water, leverages minimal control over the peptides' own form-finding program to create an entirely new class of technology.

|

|

"It's really building a bridge between the biological world," Link said, "and what until now has been the playground of synthetic chemistry."

|