| Jun 09, 2020 |

'Living bricks' create building blocks for a circular economy

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Imagine a world in which we no longer relied on the current network of drains and pipes that connect our homes to centralised waste-water treatment facilities to get rid of some of our waste liquids, like urine from toilets and grey water from washing machines. Instead, these liquids could be transformed into useful resources in our houses and businesses, such as clean water and even electricity, via a series of microbial processes, making the functioning of our buildings sustainable, circular and ‘alive’.

|

|

That is the vision of an EU-funded project called LIAR which is supported through the European Innovation Council (EIC) Pathfinder research programme, previously FET Open. It has developed the world’s first prototype system of microbe-based ‘living’ technologies capable of turning our waste back into something useful that can be integrated into buildings.

|

|

‘Our waste contains value that we currently wash and flush away. If we’re concerned about sustainability, we should be considering how we can start processing our waste at source in our homes and workplaces with microbial treatments that create resources,’ explains Rachel Armstrong, Professor of Experimental Architecture at Newcastle University in the UK and LIAR project coordinator.

|

|

Based on ecological architecture ideas, the project is at the vanguard of the concept that buildings can ‘live’ by harnessing the metabolic processes of microbes. ‘This is the foundation of a more constructive relationship with nature which will change our current way of living in passive, inert buildings,’ says Armstrong.

|

|

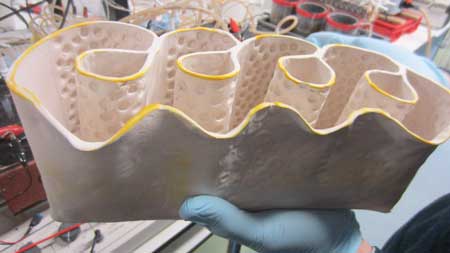

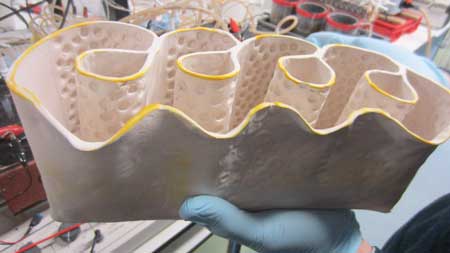

| Micro-agriculture bioreactors bring green technologies to ecological architecture. (Image: LIAR)

|

Microbes thrive on waste

|

|

LIAR scientists have developed a series of ‘living bricks’ containing bioreactors that process liquid waste. The system can link a cistern containing waste liquid to the bricks which hold three different types of chambers containing microbes that are ‘fed’ on the waste matter. Once the microbes have processed the waste, at the other end of the system, cleaned (but not yet drinkable) water is produced, as well as phosphates, biomass and electricity.

|

|

The project’s living bricks produce enough low-power electricity to charge a small device like a mobile phone. Other products include algal biomass, which can be used as compost, inorganic phosphates, which are reclaimed from laundry detergent to fertilise plants, and so-called ‘polished’ water – a cleaner form of water that needs to be filtered again before it becomes potable.

|

|

‘Our system brings nature back into buildings. It’s a bit like the revitalising feeling we get after a walk in the forest. Eventually, our technology can breathe life back into buildings where we spend most of our time, whilst also giving us value back and boosting sustainability,’ Armstrong continues.

|

Living walls

|

|

LIAR’s prototype living technologies take the form of a wall of rectangular, white and transparent bricks containing green, bubbling liquids, all interconnected by a network of tubes which Armstrong describes as ‘microbial Lego’. At this early stage of the technology, the system takes up quite a lot of space to house the necessary, interdependent microbial chambers. However, the project coordinator is already imagining sometime in the future when these living bricks could be integrated into spaces like wall cavities, carrying out liquid waste, recycling, producing valuable outputs, and acting as wall insulation.

|

|

While many of today’s appliances need 220 volts of electricity to function, she also envisages a future where fridges, washing machines and other home appliances are reinvented to run on lower, more natural levels of power – the 12 volts that could be generated by nature using LIAR’s technology.

|

|

The project has demonstrated its work at several different exhibitions in Venice, London, Tallinn and Vienna and in festivals in Japan, Norway and Denmark. LIAR’s technology is also involved in other projects, including Pee-Power® set up at the UK’s Glastonbury music festival in 2019. This 40-person urinal has lights, charging points and video games powered by microbial processes.

|

|

With the project completed, Armstrong is turning her attention to creating living architecture that works on a community level. She aims to develop a ‘wastewater garden’ that could both process sewage and generate power which could be installed near an apartment block. It would harness the value of waste across a larger scale, be capable of producing more electricity and would generate enough biomass to be used as a biofuel.

|

|

‘Our aim is to reduce and eventually eliminate our dependency on fossil-fuel-based systems in buildings, particularly as the built environment is currently responsible for 40 % of our total carbon emissions,’ she concludes.

|

|

The EIC Pathfinder programme (FET Open) fosters novel ideas to support early-stage science and technology research in exploring new foundations for radically new future technologies.

|