| Posted: Aug 04, 2014 |

New material allows for ultra-thin solar cells

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Extremely thin, semi-transparent, flexible solar cells could soon become reality. At the Vienna University of Technology, Thomas Mueller, Marco Furchi and Andreas Pospischil have managed to create a semiconductor structure consisting of two ultra-thin layers, which appears to be excellently suited for photovoltaic energy conversion ("Photovoltaic Effect in an Electrically Tunable van der Waals Heterojunction").

|

|

Several months ago, the team had already produced an ultra-thin layer of the photoactive crystal tungsten diselenide. Now, this semiconductor has successfully been combined with another layer made of molybdenum disulphide, creating a designer-material that may be used in future low-cost solar cells. With this advance, the researchers hope to establish a new kind of solar cell technology.

|

|

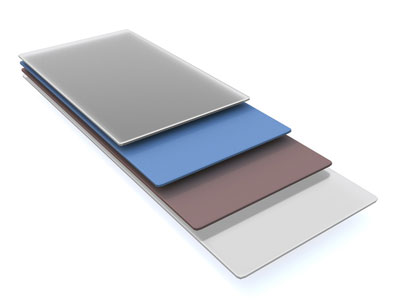

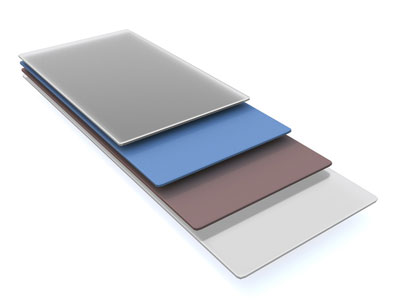

| The solar cell's layer system: two semiconductor layers in the middle, connected to electrodes on either side.

|

|

Two-Dimensional Structures

|

|

Ultra-thin materials, which consist only of one or a few atomic layers are currently a hot topic in materials science today. Research on two-dimensional materials started with graphene, a material made of a single layer of carbon atoms. Like other research groups all over the world, Thomas Mueller and his team acquired the necessary know-how to handle, analyse and improve ultra-thin layers by working with graphene. This know-how has now been applied to other ultra-thin materials.

|

|

“Quite often, two-dimensional crystals have electronic properties that are completely different from those of thicker layers of the same material”, says Thomas Mueller. His team was the first to combine two different ultra-thin semiconductor layers and study their optoelectronic properties.

|

|

Two Layers with Different Functions

|

|

Tungsten diselenide is a semiconductor which consists of three atomic layers. One layer of tungsten is sandwiched between two layers of selenium atoms. “We had already been able to show that tungsten diselenide can be used to turn light into electric energy and vice versa”, says Thomas Mueller. But a solar cell made only of tungsten diselenide would require countless tiny metal electrodes tightly spaced only a few micrometers apart. If the material is combined with molybdenium disulphide, which also consists of three atomic layers, this problem is elegantly circumvented. The heterostructure can now be used to build large-area solar cells.

|

|

When light shines on a photoactive material single electrons are removed from their original position. A positively charged hole remains, where the electron used to be. Both the electron and the hole can move freely in the material, but they only contribute to the electrical current when they are kept apart so that they cannot recombine.

|

|

To prevent recombination of electrons and holes, metallic electrodes can be used, through which the charge is sucked away - or a second material is added. “The holes move inside the tungsten diselenide layer, the electrons, on the other hand, migrate into the molybednium disulphide”, says Thomas Mueller. Thus, recombination is suppressed.

|

|

This is only possible if the energies of the electrons in both layers are tuned exactly the right way. In the experiment, this can be done using electrostatic fields. Florian Libisch and Professor Joachim Burgdörfer (TU Vienna) provided computer simulations to calculate how the energy of the electrons changes in both materials and which voltage leads to an optimum yield of electrical power.

|

|

Tightly Packed Layers

|

|

“One of the greatest challenges was to stack the two materials, creating an atomically flat structure”, says Thomas Mueller. “If there are any molecules between the two layers, so that there is no direct contact, the solar cell will not work.” Eventually, this feat was accomplished by heating both layers in vacuum and stacking it in ambient atmosphere. Water between the two layers was removed by heating the layer structure once again.

|

|

Part of the incoming light passes right through the material. The rest is absorbed and converted into electric energy. The material could be used for glass fronts, letting most of the light in, but still creating electricity. As it only consists of a few atomic layers, it is extremely light weight (300 square meters weigh only one gram), and very flexible. Now the team is working on stacking more than two layers – this will reduce transparency, but increase the electrical power.

|