| Posted: Mar 22, 2017 |

When helium behaves like a black hole

(Nanowerk News) A team of scientists has discovered that a law controlling the bizarre behavior of black holes out in space--is also true for cold helium atoms that can be studied in laboratories.

|

|

"It's called an entanglement area law," says Adrian Del Maestro, a physicist at the University of Vermont who co-led the research. That this law appears at both the vast scale of outer space and at the tiny scale of atoms, "is weird," Del Maestro says, "and it points to a deeper understanding of reality."

|

|

The new study was published in the journal Nature Physics ("Entanglement area law in superfluid 4He")--and it may be a step toward a long-sought quantum theory of gravity and new advances in quantum computing.

|

|

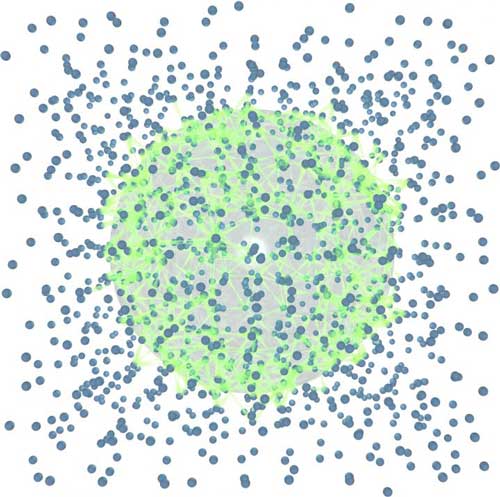

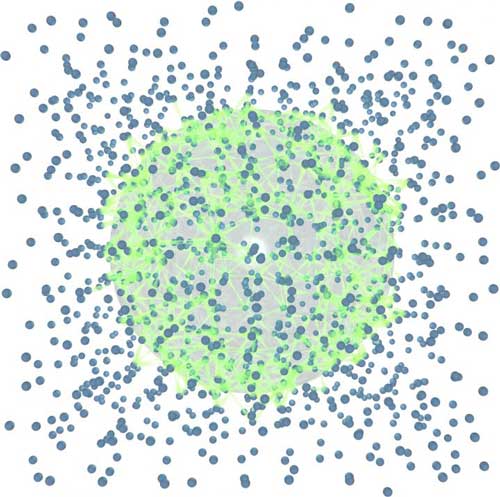

| Scientists have discovered that a sphere of cold helium atoms (in green) -- interacting with a surrounding larger container of the same kind of atoms (in blue) -- follows a bizarre rule of physics, called an entanglement area law, also observed in black holes. This discovery points to a "deeper reality," says University of Vermont physicist Adrian Del Maestro and may be a step toward using superfluid helium as the fuel of a new generation of ultra-fast quantum computers. (Image: Adrian Del Maestro)

|

At the surface

|

|

In the 1970s, famed physicists Stephen Hawking and Jacob Bekenstein discovered something strange about black holes. They calculated that when matter falls into one of these bottomless holes in space, the amount of information it gobbles up--what scientists call its entropy--increases only as fast as its surface area increases, not its volume. This would be like measuring how many files there are in a filing cabinet based on the surface area of the drawer rather than how deep the drawer is. As with many aspects of modern physics, check your common sense at the door.

|

|

"We have found the same type of law is obeyed for quantum information in superfluid helium," says Del Maestro. To make their discovery, UVM's Del Maestro and three colleagues from the University of Waterloo in Canada first created an exact simulation of the physics of extremely cold helium after it transforms from a gas into a form of matter called a superfluid: below about two degrees Kelvin, helium atoms--exhibiting the dual wave/particle nature that Max Planck and others discovered--become glopped together such that the individual atoms cannot be described independent from each other. Instead, they form a cooperative dance that the scientists call quantum entangled.

|

|

Using two supercomputers, the scientists explored the interactions of sixty-four helium atoms in a superfluid. They found that the amount of entangled quantum information shared between two regions of a container--a sphere of the helium partitioned off from the larger container--was determined by the surface area of the sphere and not its volume. Like a holograph, it seems that a three-dimensional volume of space is entirely encoded on its two-dimensional surface. Just like a black hole.

|

|

This idea had been guessed at from a principle in physics called "locality" but had never been observed before in an experiment. By using a complete numerical simulation of all the attributes of helium, the scientists were, for the first time ever, able to demonstrate the existence of the entanglement area law in a real quantum liquid.

|

|

"Superfluid helium could become an important resource--the fuel--for a new generation of quantum computers," says Del Maestro, whose work is supported by the National Science Foundation. But to make use of its huge information processing potential, he says, "we have to understand more deeply how it works."

|

Spooky neighborhoods

|

|

In the 1920s, Albert Einstein famously--and skeptically--referred to entanglement as "spooky action at a distance." Since that time, entanglement has been demonstrated as real by numerous laboratory and theoretical experiments.

|

|

Instead of defying the universe's maximum speed limit--the speed of light--what entanglement increasingly seems to show is that our human macro-scale understanding of distance, and time itself, may be illusory. A pair of entangled particles may have a quantum communication, seeming to "know" each others' state instantly across miles.

|

|

But this intuition mixes up our classical view of reality with a deeper quantum reality in which a form of information--entanglement entropy--is "delocalized," spread out in a system, with millions of possible states, or "superpositions," that only become fixed by the action of measuring. (Consider Schr?dinger's cat--both dead and alive.)

|

|

"Entanglement is non-classical information shared between parts of a quantum state," notes Del Maestro. It's "the characteristic trait of quantum mechanics that is most foreign to our classical reality."

|

|

Being able to understand, let alone control, quantum entanglement in complex systems with many particles has proven difficult. The observation of an entanglement area law in this new experiment points toward quantum liquids, like superfluid helium, as a possible medium for starting to master entanglement.

|

|

For example, the new study reveals that the density of the superfluid helium regulates the amount of entanglement. That suggests that laboratory experiments and, eventually, quantum computers could manipulate the density of a quantum liquid as a "possible knob," Del Maestro says, for regulating entanglement.

|

Hunting gravity

|

|

And this new research has implications for some fundamental problems in physics. So far, the study of gravity has largely defied efforts to bring it under the umbrella of quantum mechanics, but theorists continue to look for connections.

|

|

"Our classical theory of gravity relies on knowing exactly the shape or geometry of space-time," Del Maestro says, but quantum mechanics requires uncertainty about this shape.

|

|

A piece of the bridge between these may be formed by this new study's contribution to the "holographic principle": the exotic contention that the entire 3-D universe might be understood as two-dimensional information--whether a gargantuan black hole or microscopic puddle of superfluid helium.

|