| Jun 08, 2015 |

Research reveals key interaction that opens the channel into the cell's nucleus

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Cells have devised many structures for transporting molecular cargo across their protective borders, but the nuclear pore complex, with its flower-like, eight-fold symmetry, stands out. Monstrously large by cellular standards, as well as versatile, this elaborate portal controls access to and exit from the headquarters of the cell, the nucleus. In research published June 4 in Cell ("Allosteric Regulation in Gating the Central Channel of the Nuclear Pore Complex"), Rockefeller University scientists have uncovered crucial steps in the dynamic dance that dilates and constricts the nuclear pore complex -- the latest advance in their ongoing efforts to tease apart the mechanism by which its central channel admits specific molecules. Their work, based on quantitative biophysical data, has revealed that the nuclear pore complex is much more than the inert structure it was once thought to be.

|

|

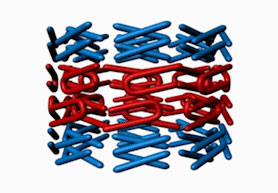

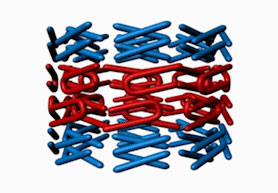

| Ring cycle: The octagonal center ring of the nuclear pore complex opens when nucleoporin 58 (red) associates with nucleoporin 54 (blue), then constricts as they separate. New research shows unstructured regions of 58 (squiggly filaments) interact with transport factors (green). This interaction makes the dilated conformation more favorable, pushing the ring to open.

|

|

"Prevailing wisdom cast the nuclear pore complex as a rigid conduit. Instead, we have found that it responds to the need for transport, opening and closing in an elegantly simple cycle," says study author Gunter Blobel, John D. Rockefeller Jr. Professor and head of the Laboratory of Cell Biology. "Our most recent study reveals how proteins called transport factors, known to chaperone legitimate cargo through the nuclear pore complex, prompt the ring at the middle of the central channel to dilate."

|

|

More than a billion years ago, certain cells gained an evolutionary advantage by surrounding their DNA in a protective membrane, creating the nucleus. However, this innovation created a problem: How to move molecules, in some cases very large ones, in and out. The nuclear pore complex was one solution, first described at Rockefeller over 50 years ago by Michael Watson, a postdoc in the Palade-Porter Laboratory. Years later, Blobel's lab identified the first of the proteins that act as the complex's building blocks: nucleoporins. For some time, it has been assumed that unstructured portions of some nucleoporin molecules guarded the complex's rigid central channel by creating a sort of gel-like barrier.

|

|

But ongoing work in Blobel's lab indicates the central channel is anything but rigid. In previous research ("Molecular Architecture of the Transport Channel of the Nuclear Pore Complex"), a team from his lab identified a flexible ring in the middle of the central channel, the diameter of which was determined by two of the nuclear pore complex's approximately 30 nucleoporins, Nup58 and Nup54, which associate and disassociate from one another in what the researchers dubbed the ring cycle. When these two nucleoporins associate, the ring dilates to a diameter of up to 50 nanometers, a size capable of accommodating a ribosomal subunit, the largest and most complex of the cell's molecular freight. Then, when the nucleoporins separate, the single ring divides into three rings with diameters of 20 nanometers.

|

|

This most recent research, conducted by postdoc Junseock Koh in Blobel's laboratory, examines how a transport factor known as karyopherin initiates the dilation of the ring. To accomplish this, Koh measured changes in heat during reactions between the three components, karyopherin, Nup58, and Nup54. Biophysical data like this reveals the energy dynamics during these reactions, and so provides clues to the behavior of the molecules involved. To tease apart this complex system, Koh mathematically analyzed the data collected at various conditions. His results revealed an unexpected role for a disordered region of Nup58.

|

|

"We found that when one karyopherin molecule binds to at least two disordered regions of Nup58, it stabilizes Nup58 in such a way that the dilated conformation -- in which the neighboring ordered region of Nup58 links up with Nup54 -- becomes more favorable. As a result, the more karyopherin molecules are present, the more the ring dilates," Koh says. "Based on these results, we were able to develop a framework for predicting the extent to which a ring will dilate given the amount of transport factors present."

|

|

"While this discovery is a critical step in understanding how the nuclear pore complex opens and closes, its implications go beyond basic cell biology", says Blobel, who is also Investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. "It is likely that even subtle problems in nuclear pore complex function may over time lead to numerous diseases."

|