| Mar 23, 2021 |

Making molecular movies of a biological process of energy conversion

(Nanowerk News) Many organisms use sunlight to fuel cellular functions. But exactly how does this conversion of solar energy into chemical energy unfold?

|

|

In a recent experiment, an international team of scientists sought answers using an advanced imaging technique called time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography to watch a pigment found in some marine bacteria as it was exposed to sunlight outside the cell.

|

|

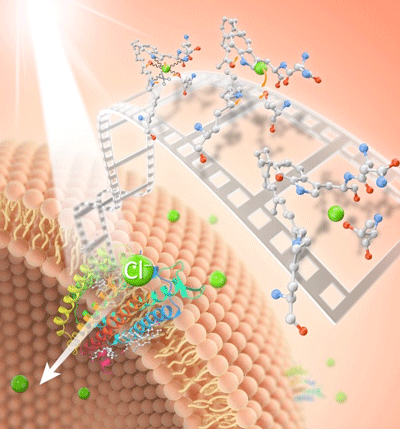

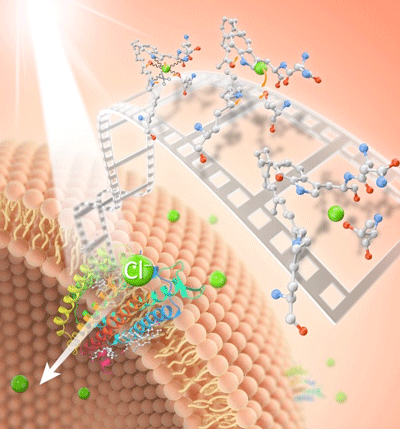

For this experiment, the researchers documented, for the first time, the dynamics of the “chloride ion-pumping rhodopsin,” an atomic “pump,” which is jump-started by sunlight and moves chloride ions unidirectionally into the bacterial cells.

|

|

These pumps may also serve as a kind of molecular solar cell for energy conversion.

|

|

Once inside, the chloride ions create a negatively charged environment, while the outside of the cell remains neutral. This results in an electric field that the bacteria could use to move, grow and maintain other vital functions.

|

|

The imaging method is capable of capturing sequential pictures of the molecular changes of biological macromolecules at work.

|

|

| Sunlight begins the process of energy generation in a marine bacterium when it jump-starts a pigment called “chloride-ion pumping rhodopsin” that moves the chloride ions (Cl-) unidirectionally into the cells. Scientists have been able to see this process for the first time, using an advanced imaging technique called time-resolved serial femtosecond crystallography, which produces molecular movies. (© PNAS)

|

|

How chloride is pumped and transported within the rhodopsin has been elusive, said Marius Schmidt, UWM professor of physics who is one of the corresponding authors on the paper, which appeared in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences ("Early-stage dynamics of chloride ion–pumping rhodopsin revealed by a femtosecond X-ray laser"). Recent UWM graduate and postdoctoral researcher Suraj Pandey also contributed substantially to this research.

|

|

“We intended to find out how sunlight drives the pump,” Schmidt said. “The rhodopsin’s response to light starts the mechanism. The response is extremely fast – at picoseconds, a trillionth of a second. So, we needed to make a molecular movie on extremely fast time scales to follow the ‘pumping’ action.”

|

|

The movie shows both the mechanics of the pump and the movements of the pump’s piston in a cylinder, which displaces the chloride ions. The size of this piston, however, is one billion times smaller than a piston in the macroscopic world. The movie shows in atomic detail how the piston pushes the chloride ions into the bacterial cell.

|

|

Imaging was done with Free Electron Laser (XFEL) equipment at the Linac Coherent Light Source in California that uses ultra-short and intense X-ray pulses that repeat rapidly to capture the frames of the molecular movie. X-rays hit protein molecules that are located in tiny crystals and which diffract into certain patterns, revealing where the atoms are at a single instance of time.

|

|

With so many pulses per second, the equipment’s camera can work at blistering speed, churning out a multitude of “snapshots.” Those are then mathematically reconstructed into 3D moving images that depict the arrangement of atoms over time – the structural changes that occur when proteins accomplish a task.

|

|

The work is relatable to human biology, he said, because the structure of the chloride pump is very similar to the rhodopsin and the photopsins in the human eye. While it doesn’t pump chloride, rhodopsin enables the human eye to absorb light and convert it into the generation of electrical signals that communicate with the brain.

|

|

The structure of this chloride-ion pump also resembles that of other G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) in humans, which regulate functions such as blood pressure and hormone management. GPRCs are of interest to the pharmaceutical industry because they are prime drug targets.

|

|

Although the imaging is being used to advance fundamental biological science, this mechanism could also be applied in the future, Schmidt said, to design light-sensitive molecular pumps. “The chloride pump could be inserted into other organisms, and you'd be able to manipulate their behavior with light through a method called optogenetics,” he said.

|