| Feb 03, 2022 |

Quantum material should be a conductor but remains an insulator

(Nanowerk News) This research (Scientific Reports, "Giant electron-phonon coupling of the breathing plane oxygen phonons in the dynamic stripe phase of La1.67Sr0.33NiO4") sheds light on the mechanism behind how a special quantum material transitions from an electrical insulator to an electricity-conducting metal.

|

|

Below a critical temperature, the subject material—lanthanum strontium nickel oxide—acts as an insulator due to the separation of introduced holes from the magnetic regions, forming “stripes.” As the temperature increases, the stripes fluctuate then “melt,” or disappear at 240 Kelvin (-28 degrees F).

|

|

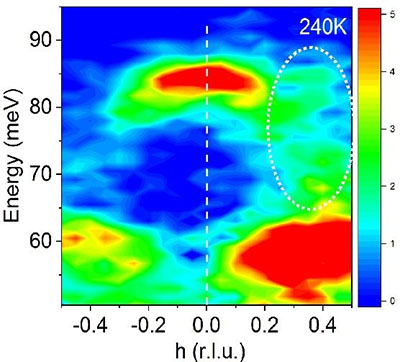

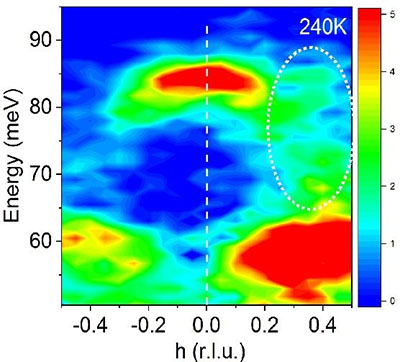

| The quantum material’s neutron scattering intensity as a function of momentum and energy. Higher intensity (red) regions are from normal atomic vibrations. Lower intensity regions (oval) indicate strong interaction between atomic vibrations and electrons. (Image: Dmitry Reznik)

|

|

While the material is expected to become metallic and conduct electricity at this temperature, it remains an insulator. To better understand the mechanism for this anomaly, the researchers conducted inelastic neutron scattering measurements. These measurements revealed that it is due to atomic vibrations that trap electrons and thus impede electrical conduction.

|

|

Quantum materials have incredible properties thanks to quantum mechanics. For example, they can change from conductors to insulators, or they can achieve superconductivity at low temperatures. This means quantum materials hold tremendous promise for applications in science and technology.

|

|

This work on the metal-to-insulator transition in lanthanum strontium nickel oxide will help to validate theoretical models of materials with strongly interacting electrons. These theories will help scientists design new quantum materials with unique properties.

|

|

In metals, electrons can be considered as free particles traveling along trajectories enforced by a material’s crystal structure. In recent decades, scientists discovered new materials in which electrons strongly repel each other and bounce off atomic vibrations in the host crystal. These materials exhibit unusual and technologically useful properties.

|

|

For example, they have dramatic drops in electrical resistance in magnetic fields, conduct electrons only on their surfaces, and are superconductive at higher temperatures. Developing a quantitative understanding of these properties is an important challenge for the scientific community.

|

|

This work used high intensity neutron beams at the Spallation Neutron Source, a Department of Energy (DOE) user facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, to look deep inside an archetype quantum material, lanthanum nickel oxide, in which one-sixth of the lanthanum atoms were replaced with strontium atoms.

|

|

This material is insulating at low temperatures due to the so-called “stripe” order that results from the complex interplay between electronic spins and the holes introduced by strontium doping. Scientists had expected that the doped material would become metallic above 240 degrees K, when the stripes melt. However, this research found that the material remains insulating.

|

|

The research uncovered strong friction between the holes and certain vibrations of oxygen ions and found evidence for this interaction in other materials with a similar structure. The microscopic mechanism could pave way for the design of new materials with unusual properties useful for quantum technologies.

|