| Oct 04, 2012 |

Bacterium in a laser trap

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Scientists from the Department of Microsystems Engineering (IMTEK) of the University of Freiburg have constructed an innovative new optical trap that can grab and scan tiny elongated bacteria with the help of a laser. The physicists Prof. Dr. Alexander Rohrbach und Matthias Koch created a kind of light tube that traps the agile unicellular organisms. Optical tweezers could previously only be used to grab bacteria at one point, not to manipulate their orientation. The Freiburg researchers have now succeeded in using a quickly moving, focused laser beam to exert an equally distributed force over the entire bacterium, which constantly changes its complex form. At the same time, they were able to record the movements of the trapped bacterium in high-speed three-dimensional images by measuring miniscule deflections of the light particles. The team reports their findings in the current online edition of Nature Photonics ("Object-adapted optical trapping and shape-tracking of energy-switching helical bacteria").

|

|

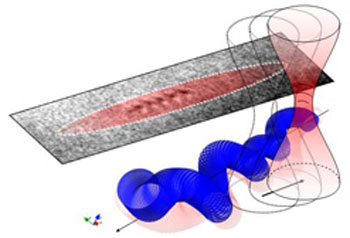

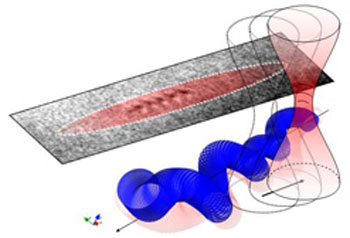

| With the innovative new optical tweezers developed by the Freiburg researchers, a quickly moving, focused laser beam holds a tiny, spiral-shaped bacterium in place and records its movements in detail. In the background is an image taken with a conventional microscope in which it is only possible to make out the bare outline of the optically trapped bacterium.

|

|

The scientists investigated so-called spiroplasmas in their study. These spiral-shaped bacteria have a diameter of only 200 nanometers, roughly equivalent to the thickness of 1,000 atoms. Since they do not have a cell wall, they can rapidly change their shape and move. It is not possible to observe these bacteria sufficiently through a conventional optical microscope due to their small size and their rapid movements. Using the newly developed light-scanning optical trap, however, the biophysicists were able to hold and orient the bacteria over their entire length.

|

|

One important attribute of laser light is that overlapping light particles can increase or decrease the brightness of the beam. When light hits and is deflected from the bacterium it overlaps with the non-deflected light and thus becomes stronger, enabling the creation of three-dimensional images that are not only high in contrast but also in resolution. In this way, the researchers were able to take up to 1,000 three-dimensional images per second and record the rapid movements of the bacterium in detail in a movie (see link).

|

|

“This is fascinating in a physical sense, because the movements of the bacteria are connected with extremely small changes in energy that are usually almost impossible to measure,” says Rohrbach, a member of the Cluster of Excellence BIOSS, the Centre for Biological Signalling Studies of the University of Freiburg. This makes the discovery into a practical tool for fundamental research. “Interesting from a biological point of view are the signals that the bacterium sends out when it changes shape, because they provide clues about the molecular processes going on inside of it – for instance as a reaction to stress states the bacterium has been subjected to.”

|

|

In the future, the Freiburg scientists plan to use this method to study the behavior and cellular mechanics of other bacteria that do not have a cell wall and that are therefore difficult to treat with antibiotics. These studies could thus help scientists to reach a better understanding of bacterial infectious diseases.

|