| Jun 06, 2013 |

Artificial 'cricket hair' sensor uncovers hidden signals

|

|

(Nanowerk News) An “artificial cricket hair” used as a sensitive flow sensor has difficulty detecting weak, low-frequency signals – they tend to be drowned out by noise. But now, a bit of clever tinkering with the flexibility of the tiny hair’s supports has made it possible to boost the signal-to-noise ratio by a factor of 25. This in turn means that weak flows can now be measured. Researchers at the MESA+ Institute for Nanotechnology of the University of Twente (NL) have presented details of this technology in the New Journal of Physics ("Uncovering signals from measurement noise by electro mechanical amplitude modulation").

|

|

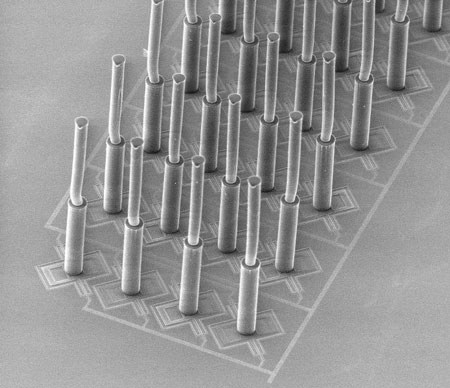

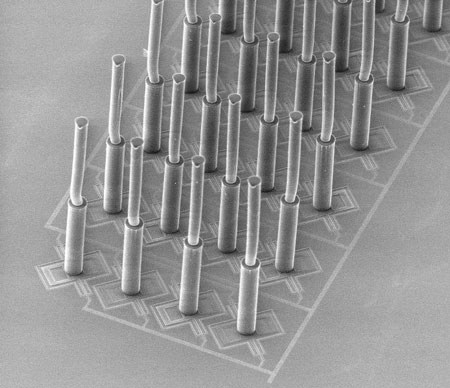

| Tiny “hairs” of the polymer SU-8 are applied to a flexible, moving surface, the capacitance of which changes with each movement.

|

|

These tiny hairs, which are manufactured using microtechnology techniques, are neatly arranged in rows and mimic the extremely sensitive body hairs that crickets use to detect predators. When a hair moves, the electrical capacitance at its base changes, making the movement measurable. If there is an entire array of hairs, then this effect can be used to measure flow patterns. In the same way, changes in air flow tell crickets that they are about to be attacked.

|

|

Mechanical AM radio

|

|

In the case of low-frequency signals, the noise inherent to the measurement system itself tends to throw a spanner in the works by drowning out the very signals that the system was designed to measure. One very appealing idea is to “move” these signals into the high frequency range, where noise is a much less significant factor. The MESA+ researchers achieve this by periodically changing the hairs’ spring rate. They do so by applying an electrical voltage.

|

|

This adjustment also causes the hairs to vibrate at a high frequency. This resembles the technology used in old AM radios, where the music signal is encoded on a higher frequency wave. In the case of the sensor, its “radio” is a mechanical device. Low frequency flows are measured by tiny hairs vibrating at a higher frequency. The signal can then be retrieved, with significantly less noise. Suddenly, a previously unmeasurable signal emerges, thanks to this “up-conversion".

|

|

This electromechanical amplitude modulation (EMAM) expands the hair sensors’ range of applications enormously. Now that the signal-to-noise ratio has been improved by a factor of 25, it is possible to measure much weaker signals.

According to the researchers, this technology could be a very useful way of boosting the performance of many other types of sensors.

|