| Posted: July 25, 2006 |

Researchers explore using nanotubes as minuscule metalworking tools |

|

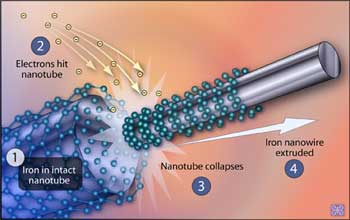

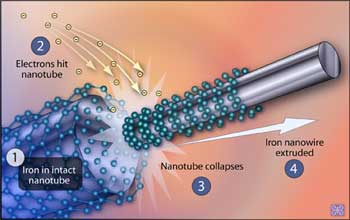

(Nanowerk News) Bombarding a carbon nanotube with electrons causes it to collapse with such incredible force that it can squeeze out even the hardest of materials, much like a tube of toothpaste, according to an international team of scientists. Reporting in the May 26 issue of the journal Science, the researchers suggest that carbon nanotubes can act as minuscule metalworking tools, offering the ability to process materials as in a nanoscale jig or extruder.

|

|

Engineers use a variety of tools to manipulate and process metals. For example, handy “jigs” control the motion of tools, and extruders push or draw materials through molds to create long objects of a fixed diameter. The newly reported findings suggest that nanotubes could perform similar functions at the scale of atoms and molecules, the researchers say.

|

|

The results also demonstrate the impressive strength of carbon nanotubes against internal pressure, which could make them ideal structures for nanoscale hydraulics and cylinders. In the experiments, nanotubes withstood pressures as high as 40 gigapascals, just an order of magnitude below the roughly 350 gigapascals of pressure at the center of the Earth.

|

|

When a beam of electrons hits a carbon nanotube, some carbon atoms are knocked away, causing the remaining atoms to contract and the tube to shrink. When the tube is filled with even incredibly hard substances like iron carbide, the contraction squeezes the substance out as ultra-thin wires. (Source: Zina Deretsky, National Science Foundation)

|

|

“Researchers will need a wide range of tools to manipulate structures at the nanoscale, and this could be one of them,” says Pulickel Ajayan, the Henry Burlage Professor of Materials Science and Engineering at Rensselaer and an author of the paper. “For the time being our work is focused at the level of basic research, but certainly this could be part of the nanotechnology tool set in the future.”

|

|

The current paper is the latest result from Ajayan’s longtime collaboration with researchers at Johannes Gutenberg University in Mainz, Germany; the Institute for Scientific and Technological Research (IPICyT) of San Luis Potosi, Mexico; and the University of Helsinki in Finland. Florian Banhart of the Institute of Physical Chemistry at Johannes Gutenberg University is the lead corresponding author of the May 26 Science paper.

|

|

Carbon nanotubes have been hailed as some of the lightest, strongest materials ever made, and they are beginning to find use in a wide variety of materials. Yet while many of their distinctive properties have been studied in detail, the strength of carbon nanotubes against large internal pressures has yet to be fully explored, according to the researchers.

|

|

The research builds on the team’s earlier findings detailing how bombarding electrons at carbon “onions” — tiny, multilayered balls of carbon — essentially knocks the carbon atoms out of their lattice. Surface tension then causes the balls to contract with great force, which allows carbon onions to act as high-pressure cells for creating diamonds.

|

|

In the new report, the team discovered that the same thing happens with nanotubes, producing enough pressure to deform, extrude, and even break solid materials that are encapsulated within.

|

|

The researchers filled carbon nanotubes with nanowires made from two extremely hard materials: iron and iron carbide. When irradiated with an electron beam, the collapsing nanotubes squeezed the materials through the hollow core along the tube axis, as in an extrusion process. In one test, the diameter of iron carbide wire decreased from 9 nanometers to 2 nanometers as it moved through the tube, only to be pinched off when the nanotube finally collapsed.

|

|

These jigs could be perfect nanoscale laboratories to study the effects of deformation in nanostructures by observing them directly in an electron microscope, the authors suggest. An electron microscope from Johannes Gutenberg University was used for the experiment, which allowed the researchers to watch the extrusion process proceed in real-time at high resolution.

|