| Oct 02, 2012 |

Light at atomic dimensions

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Physicists of the University of Würzburg have succeeded in concentrating light in an inconceivably small area. They took advantage of an effect that also occurs when coffee is spilled ("Atomic-scale confinement of resonant optical fields").

|

|

Visible light is the part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is most important to our everyday perception. The fact that our environment is colored and that we are able to perceive these colors is due to the characteristic interaction between visible photons and matter.

|

|

This interaction allows conclusions on the properties of matter, for which reason optical microscopy plays a prominent role in the exploration of the nanocosm. Furthermore, light is important for many applications, such as data storage – as known from its use in DVD and Blue-Ray media – optical data transmission and data processing in the Internet.

|

|

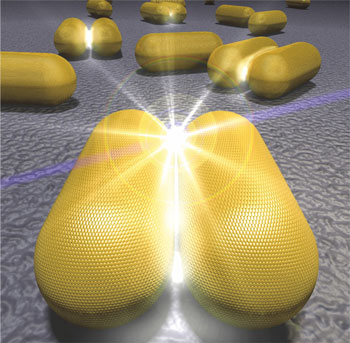

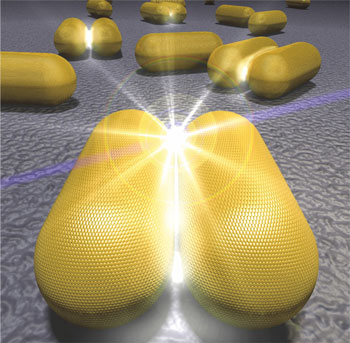

| Artistic representation of two gold nanorods with a strongly localized optical field in an atomic-scale air gap. (Graphics: Thorsten Feichtner)

|

|

Spatial concentration is essential

|

|

In all above-mentioned fields, the spatial confinement of visible light to the smallest possible dimensions is of crucial importance. The stronger the concentration or focusing of the light is, e.g. in optical microscopy, the higher the resolution and the smaller the structures that can be examined will be. In optical data processing, this makes an ongoing miniaturization and integration possible, which leads to higher data transfer rates.

|

|

"Unfortunately, the spatial concentration of light in free space has its natural limits set by diffraction effects," says Professor Bert Hecht. "The spatial resolution in microscopy and the storage density of optical media are limited by diffraction if only conventional components, such as lenses or mirrors, are used." Therefore, the physicist and his study group at the Department of Experimental Physics 5 have long been seeking new ways of confining light to the smallest possible dimensions. They have now achieved a breakthrough, working together with colleagues from engineering physics.

|

|

Brave the (atomic) gap

|

|

"We succeeded in focusing light down to atomic dimensions by means of plasmonic nanostructures," explains Hecht. Plasmonic nanostructures: This is a term used by physicists referring to structures in which freely movable, negatively charged electrons perform resonant oscillations against the background of stationary, positively charged atomic cores. These oscillations give rise to periodically alternating excess charges at the surface of the structures, in turn producing alternating electrical fields. "Since these alternating fields change their sign in accordance with the optical frequency, they represent surface-bound light fields," the physicist says.

|

|

As reported in the current online edition of the prestigious journal "NanoLetters", the study group of Bert Hecht managed for the first time to localize such surface-bound fields accurately in an experiment in the extremely small gap between two adjacent plasmonic gold nanostructures. The relevant gap has the smallest possible width, which corresponds approximately to the distance of two atoms in a gold crystal. This corresponds to a light spot that is a thousand times smaller than the respective wavelength of the light.

|

|

The nanostructures required for this experiment were created by the physicists in a remarkably simple process. The scientists used chemically grown gold rods, each of them only about 30 nanometers in diameter and about 70 nanometers in length – a nanometer is equal to one millionth of a millimeter. These rods were dissolved in water, droplets of which were then applied to a glass carrier. Due to an effect that is also present in the formation of coffee rings, pairs of laterally aligned gold nanorods assemble themselves automatically at the edge of the droplet, moving closer to each other during the evaporation of the liquid until no more than an atomic-scale gap is left.

|

|

In their experiments, the Würzburg researchers irradiated these rod pairs with white light and examined the colors of the scattered light. From the characteristic spectral position of the color components in the scattered light, the researchers were able to infer the resonant oscillation states of the electrons, thus deducing a concentration of the light in the gap between the gold rods.

|

|

Possible applications

|

|

"Such strongly concentrated optical fields offer a variety of possible applications," explains Johannes Kern, doctoral student in the study group of Bert Hecht and lead author of the publication. "Further developments include optical microscopy or the reading of storage media with atomic resolution." New possibilities open up in other application areas as well: The extremely strong concentration of light goes hand in hand with a local amplification of the optical fields, which not only allows an optimization of the light absorption process, which is of fundamental importance in photovoltaics, but it could also help generate non-linear optical processes that might in future be used for the creation of optical single-photon transistors in optical nanocircuits.

|