| Feb 14, 2013 |

Nanosensors support skin cancer therapy

|

|

(Nanowerk News) Malignant melanoma is the most aggressive type of skin cancer. In more than 50 percent of affected patients a particular mutation plays an important role. As the life span of the patients carrying the mutation can be significantly extended by novel drugs, it is very important to identify those reliably. For identification, researchers from the University of Basel and the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne have developed a novel method, as they report in the renowned journal Nature Nanotechnology ("Direct detection of a BRAF mutation in total RNA from melanoma cells using cantilever arrays").

|

|

In Switzerland, every year about 2100 persons are affected by malignant melanoma, which makes it one of the most frequent tumors. While early detected the prospects of recovery are very good, in contrast at later stages the chances of survival are reduced drastically.

|

|

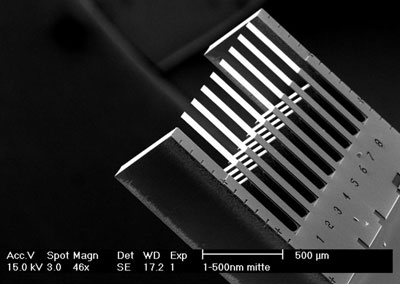

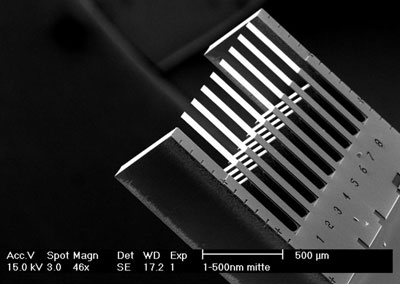

| Nanosensor: Eight cantilevers of 500 ?m in length are applied for detection of the genetic mutation.

|

|

In the past few years, several novel drugs have been developed that take advantage of the presence of particular genetic mutations related to fast cell growth in tissue. In case of melanoma, the so-called BRAF gene is of importance, which leads in its mutated state to uncontrolled cell growth. Since only about 50 percent of patients with malignant melanoma show this mutation, it is important to identify those patients who respond to the novel therapy. Taking into account the negative side effects of the drug, it would not be appropriate to apply the drug to all patients.

|

|

Diagnosis involving molecular interaction

|

|

The teams of Prof. Christoph Gerber from the Swiss Nanoscience Institute of the University of Basel and Dr. Donata Rimoldi from the Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research in Lausanne have recently developed a novel diagnostic method that analyzes the ribonucleic acid (RNA) of cancer cells using nanomechanical sensors, i.e. microscopically small cantilevers. Thus, healthy cells can be distinguished from cancer cells. In contrast to other methods, the cantilever approach is so sensitive that neither DNA needs to be amplified nor labeled.

|

|

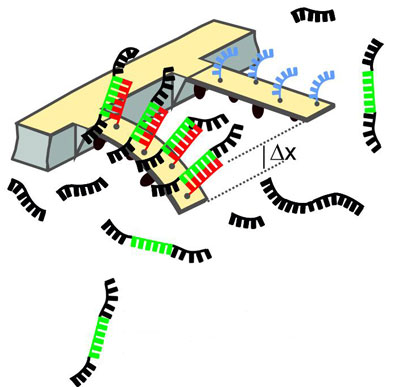

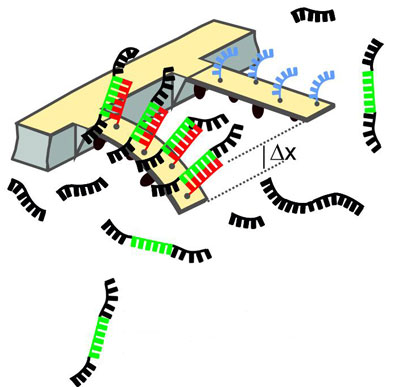

The method is based on binding of molecules to the top surface of a cantilever and the related change in surface stress. For this purpose the cantilevers are first coated with a layer of DNA molecules which can bind mutated RNA from cells. The binding process deflects the cantilever. The bending is measured using a laser beam. The molecular interaction must take place very close to the cantilever surface to produce a signal.

|

|

| Schematic of the method: When the mutated RNA molecules (green) bind to DNA molecules (red), the cantilever will bend. The deflection is measured using a laser.

|

|

Detection of other types of cancer

|

|

In experiments the researchers could show that cells carrying this genetic mutation can be distinguished from others lacking the mutation. RNA of cells from a cell culture was tested in concentrations similar to those in tissue samples. Since the researchers could detect the mutation in RNA stemming from different cell lines, the method actually works independent of the origin of samples.

|

|

Dr. François Huber, first author of the publication, explains: "The technique can also be applied to other types of cancer that depend on mutations in individual genes, for example in gastrointestinal tumors and lung cancer. This shows the wide application potential in cancer diagnostics and personalized health care." Co-author Dr. Donata Rimoldi adds: "Only the interdisciplinary approach in medicine, biology and physics allows to apply novel nanotechnology methods in medicine for the benefit of patients."

|

|

The work was supported by the NanoTera project "Probe Array Technology for Life Science Applications" of the Swiss National Science Foundation, by the Swiss Nanoscience Institute, the Cleven foundation and the microfabrication division of IBM Research in Rüschlikon.

|