| Posted: Dec 16, 2014 |

Waves, folds and plastic flow: detecting the first signs of wear on metal surfaces

|

|

(Nanowerk News) A great deal of scientific research has been carried out on minimizing wear in metal-based systems. Most of this work focused on the phenomenological level. Low-wear metal surfaces will, however, only be achieved if one has a fundamental understanding of the processes involved in friction at the atomic level.

|

|

A team of expert scientists led by Prof. Dr. Michael Moseler and Prof. Dr. Peter Gumbsch at the Fraunhofer Institute for Mechanics of Materials IWM in Freiburg has carried out a large-scale atomistic material 3D computer simulation and succeeded in visualizing the nanoscale mechanisms involved in the friction process on a polycrystalline metal surface before the wear actually becomes visible. In order to reduce friction and wear, one must cope with these mechanisms. Experiments carried out by a group headed by Martin Dienwiebel from the Microtribology Center µTC confirm the IWM’s computer simulation findings.

|

|

The Fraunhofer IWM scientists are presenting their results in the current issue of Physical Review Applied ("Origins of Folding Instabilities on Polycrystalline Metal Surfaces").

|

|

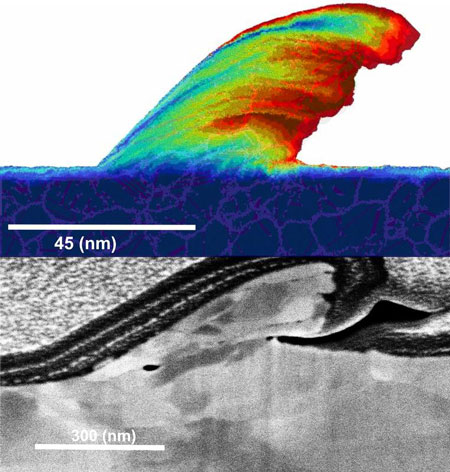

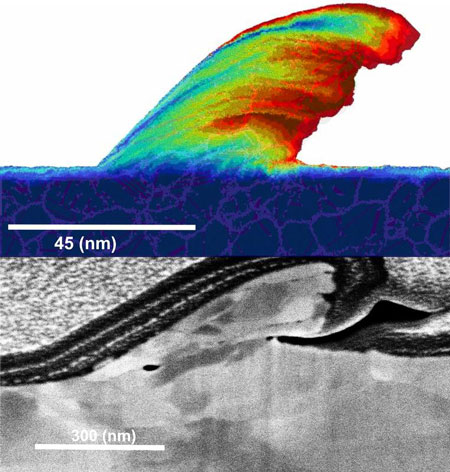

| Chip created on the surface of polycrystalline copper after scratching with a hard tip: simulation and experiment. (Image: Fraunhofer IWM)

|

|

The Institute for Applied Materials at the KIT Karlsruhe, Robert Bosch GmbH and the Institute for Physics at the University of Freiburg were also involved in the project. The researchers were inspired to carry out their simulation by an experiment at the Center for Materials Processing and Tribology at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana [N.K. Sundaram et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 1065001 (2012)]. In this experiment, the scientists from Purdue scratched a copper surface using a hard tip and observed how this created a “wave” of folded copper ahead of the tip. This demonstrated that the metal was subject to plastic deformation flow, which can either appear laminar or turbulent, as in liquids. The Fraunhofer IWM researchers went one step further: they investigated and assessed the plastic flow at the atomic level and made some interesting discoveries.

|

|

Crystal grain orientation plays an important role

|

|

The Fraunhofer IWM performed a virtual, nanoscale re-enactment of the American experiment using computer software to create a simulation based on 15 million copper atoms.

|

|

“On an experimental level, an analogy to the Kelvin-Helmholtz instability in fluids was quickly established to describe what was going on,” says Michael Moseler, but in the light of the Fraunhofer IWM’s findings this hydrodynamic picture is no longer appropriate.

|

|

Instead, the computer simulation showed that different grain orientations in the polycrystalline metal structure are responsible for the folds and swirls. The simulation made it possible to see each individual grain and proved that some grains yield readily while others resist the abrasive pressure, depending on crystal orientation.

|

|

“The folds therefore always occur at the grain boundary,“ Moseler goes on to explain. One can also see that the grains can deform to a different extent and can join together to form larger grains.

|

|

Folds and impurities in the material create lamellar wear particles

|

|

By coloring the atomic layers of the metal surface differently, the scientists at the Fraunhofer IWM could also illustrate how the shearing dynamics cause atoms from the surface to penetrate deep into the material. In a second step, the researchers simulated the tip passing back over the metal chip, thus mimicking the actual dynamics in an oscillating tribological contact. The previously generated folds proceeded to lie down on the material as lamellae. An interesting aspect here is that this process embeds impurities, such as oxides, from the metal surface between the lamellae. “It is very similar to puff pastry!“ explains Moseler. The impurities make the metal instable and explain why lamellar wear particles are produced during the wear process.

|

|

“Previously, one had assumed it was due to material fatigue,“ says Moseler.

|

|

“We have shown that grains at the surface react in different ways,“ says the Fraunhofer IWM’s Prof. Dr. Peter Gumbsch, adding “in our subsequent research work, we will focus on establishing the ideal grain orientation that prevents folds from even forming, keeping potential applications in mind.“

|

|

Mechanical surface treatment or targeted doping to influence grain boundaries are possible means of establishing this ideal grain orientation. The Fraunhofer IWM computer simulation is based on copper, but can be translated to many other metals.

|

|

According to Gumbsch, “our findings can be used by development engineers, to establish design guidelines that make it possible to precisely establish a grain structure which meets the mechanical requirements for metals that are subject to tribological loads.”

|