Showing Spotlights 89 - 96 of 110 in category All (newest first):

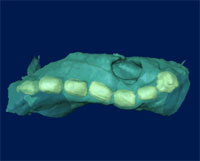

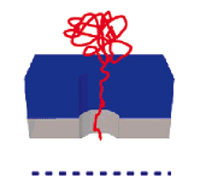

Understanding and manipulating cellular function at the level of individual molecules is within reach. One of the requirements of single molecule techniques is the ability to follow an individual molecule for sufficiently long times in solution. However, it is a challenge to cope with the effects of Brownian motion (the random motion of small particles suspended in a gas or liquid) on this time scale. To meet this challenge, more recently, biomolecules have been encapsulated inside lipid vesicles, which are themselves tethered to a surface. Now, a novel nanocontainer offers controlled permeability functionality which not only is desirable for single molecule imaging but also is a very important property for micro- and nanodevices and for delivery of drugs or imaging agents in vitro and in vivo.

Understanding and manipulating cellular function at the level of individual molecules is within reach. One of the requirements of single molecule techniques is the ability to follow an individual molecule for sufficiently long times in solution. However, it is a challenge to cope with the effects of Brownian motion (the random motion of small particles suspended in a gas or liquid) on this time scale. To meet this challenge, more recently, biomolecules have been encapsulated inside lipid vesicles, which are themselves tethered to a surface. Now, a novel nanocontainer offers controlled permeability functionality which not only is desirable for single molecule imaging but also is a very important property for micro- and nanodevices and for delivery of drugs or imaging agents in vitro and in vivo.

Mar 18th, 2008

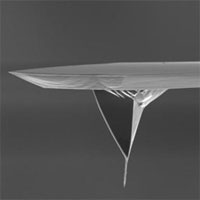

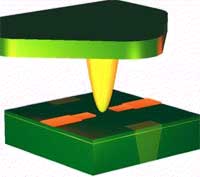

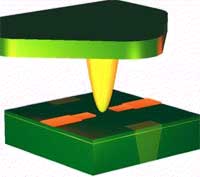

Discover AFM's role in nanotechnology with our in-depth guide on its working principle, applications, and future trends in nanoscale imaging and characterization.

Discover AFM's role in nanotechnology with our in-depth guide on its working principle, applications, and future trends in nanoscale imaging and characterization.

Mar 10th, 2008

The need for 3D visualization and analysis at high spatial resolution is likely to increase as nanoscience and nanotechnology become increasingly important and nanotomography could play a key role in understanding structure, composition and physico-chemical properties at the nanoscale. Scientists from the Electron Microscopy Group at the University of Cambridge in the UK report that nanotomography is becoming an important tool in the study of the size, shape, distribution and composition of various materials, including nanomaterials.

The need for 3D visualization and analysis at high spatial resolution is likely to increase as nanoscience and nanotechnology become increasingly important and nanotomography could play a key role in understanding structure, composition and physico-chemical properties at the nanoscale. Scientists from the Electron Microscopy Group at the University of Cambridge in the UK report that nanotomography is becoming an important tool in the study of the size, shape, distribution and composition of various materials, including nanomaterials.

Oct 2nd, 2007

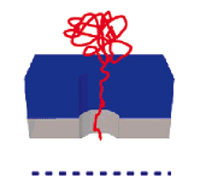

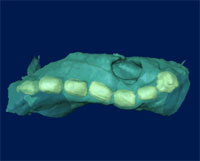

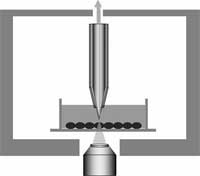

There is a significant and growing need across the research and medical communities for low-cost, high throughput DNA separation and quantification techniques. The isolation of DNA is a prerequisite step for many molecular biology techniques and experiments. Although single molecule techniques afford extremely high sensitivity, to date, such experiments have remained within the confines of academic and research laboratories. The primary reasons for this state of affairs relate to throughput, detection efficiencies and analysis times. For example, in a conventional solution-based single molecule detection experiment, one can only detect approximately 10,000 molecules per minute, or one molecule every 6 milliseconds. While this may sound a lot, consider that a small drop of water (ca. 5 ml) contains approx. 1.67 x 10e23 molecules, that is 1.67 followed by 23 zeros. At that speed you need over 100 trillion years to detect all the water molecules in this single drop. Using a novel nanopore array developed by researchers in the UK, expect to be able to detect up to 1 million molecules simultaneously in the same 6 millisecond time window, representing an improvement in throughput of over six orders of magnitude (and bringing the timeframe for analyzing the molecules in a single water drop down to some 60 billion years - about five to six times the estimated age of the universe).

There is a significant and growing need across the research and medical communities for low-cost, high throughput DNA separation and quantification techniques. The isolation of DNA is a prerequisite step for many molecular biology techniques and experiments. Although single molecule techniques afford extremely high sensitivity, to date, such experiments have remained within the confines of academic and research laboratories. The primary reasons for this state of affairs relate to throughput, detection efficiencies and analysis times. For example, in a conventional solution-based single molecule detection experiment, one can only detect approximately 10,000 molecules per minute, or one molecule every 6 milliseconds. While this may sound a lot, consider that a small drop of water (ca. 5 ml) contains approx. 1.67 x 10e23 molecules, that is 1.67 followed by 23 zeros. At that speed you need over 100 trillion years to detect all the water molecules in this single drop. Using a novel nanopore array developed by researchers in the UK, expect to be able to detect up to 1 million molecules simultaneously in the same 6 millisecond time window, representing an improvement in throughput of over six orders of magnitude (and bringing the timeframe for analyzing the molecules in a single water drop down to some 60 billion years - about five to six times the estimated age of the universe).

Sep 4th, 2007

In the early 1870s, the German physicist Ernst Karl Abbé formulated a rigorous criterion for being able to resolve two objects in a light microscope. According to his equation, the best resolution achievable with visible light is about 200 nanometers. This theoretical resolution limit of conventional optical imaging methodology was the primary factor motivating the development of recent higher-resolution scanning probe techniques. The interaction of light with an object results in the generation of what is called 'near-field' and 'far-field' light components. The far-field light propagates through space in an unconfined manner and is the visible light utilized in conventional light microscopy. The near-field (or evanescent) light consists of a nonpropagating field that exists near the surface of an object at distances less than a single wavelength of light. So called near-field microscopy beats light's diffraction limit by moving the source very close to the subject to be imaged. When the first theoretical work on a new technique called "scanning near-field optical microscopy" (SNOM or NSOM) appeared in the 1980's, Abbé's classical diffraction limit was overcome, and resolution even down to single molecule level became feasible. However, light microscopy is still the only way to observe the interior of whole, or even living, cells. The use of fluorescent dyes makes it possible to selectively obtain images of individual cell components, for example, proteins. Today, the wavelength dogma has been overcome with the development of the stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope. Now, the German team that developed STED is reporting layer-by-layer light microscopic nanoscale images of cells and without having to prepare thin sections with a technique called optical 3D far-field microscopy. They use a chemical marker for fluorescence nanoscopy that relies on single-molecule photoswitching.

In the early 1870s, the German physicist Ernst Karl Abbé formulated a rigorous criterion for being able to resolve two objects in a light microscope. According to his equation, the best resolution achievable with visible light is about 200 nanometers. This theoretical resolution limit of conventional optical imaging methodology was the primary factor motivating the development of recent higher-resolution scanning probe techniques. The interaction of light with an object results in the generation of what is called 'near-field' and 'far-field' light components. The far-field light propagates through space in an unconfined manner and is the visible light utilized in conventional light microscopy. The near-field (or evanescent) light consists of a nonpropagating field that exists near the surface of an object at distances less than a single wavelength of light. So called near-field microscopy beats light's diffraction limit by moving the source very close to the subject to be imaged. When the first theoretical work on a new technique called "scanning near-field optical microscopy" (SNOM or NSOM) appeared in the 1980's, Abbé's classical diffraction limit was overcome, and resolution even down to single molecule level became feasible. However, light microscopy is still the only way to observe the interior of whole, or even living, cells. The use of fluorescent dyes makes it possible to selectively obtain images of individual cell components, for example, proteins. Today, the wavelength dogma has been overcome with the development of the stimulated emission depletion (STED) microscope. Now, the German team that developed STED is reporting layer-by-layer light microscopic nanoscale images of cells and without having to prepare thin sections with a technique called optical 3D far-field microscopy. They use a chemical marker for fluorescence nanoscopy that relies on single-molecule photoswitching.

Aug 13th, 2007

Children begin to learn by seeing, hearing, tasting and, above all, by touching. In a very similar approach, we are currently learning to orient ourselves in the nanoworld by 'feeling' materials - not with our fingers, but with microscopes that allow us to probe these materials with atomic resolution.

Children begin to learn by seeing, hearing, tasting and, above all, by touching. In a very similar approach, we are currently learning to orient ourselves in the nanoworld by 'feeling' materials - not with our fingers, but with microscopes that allow us to probe these materials with atomic resolution.

Aug 7th, 2007

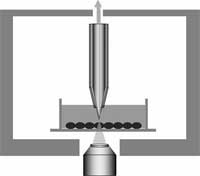

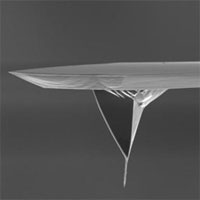

You might remember our Spotlight from a few months ago (25 years of scanning probe microscopy and no standards yet) where we gave an overview of how scanning probe microscopy has flourished over the past 25 years. The most versatile implementation of the scanned probe principle is the atomic force microscope (AFM). It has become one of the foremost tools for imaging, measuring and manipulating matter at the nanoscale. The essential part of an AFM is a microscale cantilever with a sharp tip (probe) at its end that is used to scan the specimen surface. The cantilever is typically silicon or silicon nitride with a tip radius of curvature on the order of nanometers. When the tip is brought into proximity of a sample surface, forces between the tip and the sample lead to a deflection of the cantilever according to Hooke's law. A multi-segment photodiode measures the deflection via a laser beam, which is reflected on the cantilever surface. Because there are so many promising areas in nanotechnology and biophysics which can be examined by AFM (force spectroscopy on DNA, muscle protein titin, polymers or more complex structures like bacteria flagella, 3-D imaging, etc. ) the availability of instruments is crucial, especially for new groups and young scientists with limited funds. The price tag of AFMs runs in the hundreds of thousand s of dollars, though. Until now, AFM heads are made of metal materials by conventional milling, which restricts the design and increases the costs. German researchers have shown that rapid prototyping can be a quicker and less costly alternative to conventional manufacturing.

You might remember our Spotlight from a few months ago (25 years of scanning probe microscopy and no standards yet) where we gave an overview of how scanning probe microscopy has flourished over the past 25 years. The most versatile implementation of the scanned probe principle is the atomic force microscope (AFM). It has become one of the foremost tools for imaging, measuring and manipulating matter at the nanoscale. The essential part of an AFM is a microscale cantilever with a sharp tip (probe) at its end that is used to scan the specimen surface. The cantilever is typically silicon or silicon nitride with a tip radius of curvature on the order of nanometers. When the tip is brought into proximity of a sample surface, forces between the tip and the sample lead to a deflection of the cantilever according to Hooke's law. A multi-segment photodiode measures the deflection via a laser beam, which is reflected on the cantilever surface. Because there are so many promising areas in nanotechnology and biophysics which can be examined by AFM (force spectroscopy on DNA, muscle protein titin, polymers or more complex structures like bacteria flagella, 3-D imaging, etc. ) the availability of instruments is crucial, especially for new groups and young scientists with limited funds. The price tag of AFMs runs in the hundreds of thousand s of dollars, though. Until now, AFM heads are made of metal materials by conventional milling, which restricts the design and increases the costs. German researchers have shown that rapid prototyping can be a quicker and less costly alternative to conventional manufacturing.

Aug 1st, 2007

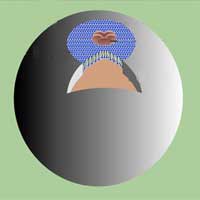

Cells are the smallest 'brick' in life's building structures. Every living organism is made of cells. Individual cells carry their own DNA and have their own life cycle. Considering that larger organisms, such as humans, are basically huge, organized cell cooperatives, the study of individual live cells is a hugely important scientific task. Among the most significant technical challenges for performing successful live-cell imaging experiments is to maintain the cells in a healthy state and functioning normally on the microscope stage while being illuminated. Especially if scientists want to look into cellular processes that occur in cells in their natural state and that cannot be observed by traditional cytological methods. It is well known that cells move, grow, duplicate, and move from point A to point B. Up to now people studied these mechanical properties with optical microscopes because it is the most common and simple method, very efficient, a very well developed and advanced technology. However, with optical microscopes detection is limited to objects no smaller than the wavelengths of the visible region of light, roughly between 400 and 700 nanometers. Distances or movement smaller than this range cannot be seen with these instruments. Researchers in Kyoto, Japan have applied a near-field optical approach to measure cell mechanics and were able to show intriguing data of nanoscale cell membrane dynamics associated with different phenomena of the cell's life, such as cell cycle and cell death.

Cells are the smallest 'brick' in life's building structures. Every living organism is made of cells. Individual cells carry their own DNA and have their own life cycle. Considering that larger organisms, such as humans, are basically huge, organized cell cooperatives, the study of individual live cells is a hugely important scientific task. Among the most significant technical challenges for performing successful live-cell imaging experiments is to maintain the cells in a healthy state and functioning normally on the microscope stage while being illuminated. Especially if scientists want to look into cellular processes that occur in cells in their natural state and that cannot be observed by traditional cytological methods. It is well known that cells move, grow, duplicate, and move from point A to point B. Up to now people studied these mechanical properties with optical microscopes because it is the most common and simple method, very efficient, a very well developed and advanced technology. However, with optical microscopes detection is limited to objects no smaller than the wavelengths of the visible region of light, roughly between 400 and 700 nanometers. Distances or movement smaller than this range cannot be seen with these instruments. Researchers in Kyoto, Japan have applied a near-field optical approach to measure cell mechanics and were able to show intriguing data of nanoscale cell membrane dynamics associated with different phenomena of the cell's life, such as cell cycle and cell death.

Jun 11th, 2007

Understanding and manipulating cellular function at the level of individual molecules is within reach. One of the requirements of single molecule techniques is the ability to follow an individual molecule for sufficiently long times in solution. However, it is a challenge to cope with the effects of Brownian motion (the random motion of small particles suspended in a gas or liquid) on this time scale. To meet this challenge, more recently, biomolecules have been encapsulated inside lipid vesicles, which are themselves tethered to a surface. Now, a novel nanocontainer offers controlled permeability functionality which not only is desirable for single molecule imaging but also is a very important property for micro- and nanodevices and for delivery of drugs or imaging agents in vitro and in vivo.

Understanding and manipulating cellular function at the level of individual molecules is within reach. One of the requirements of single molecule techniques is the ability to follow an individual molecule for sufficiently long times in solution. However, it is a challenge to cope with the effects of Brownian motion (the random motion of small particles suspended in a gas or liquid) on this time scale. To meet this challenge, more recently, biomolecules have been encapsulated inside lipid vesicles, which are themselves tethered to a surface. Now, a novel nanocontainer offers controlled permeability functionality which not only is desirable for single molecule imaging but also is a very important property for micro- and nanodevices and for delivery of drugs or imaging agents in vitro and in vivo.

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed

Subscribe to our Nanotechnology Spotlight feed